Fairy Tales of Truth

Why we need bedtime stories

We live in a practical world. It’s very much geared towards the key pillars of the workplace; our lifestyle, our past-times, our education, they’re all very… vocational. The modern curriculum is heavily in favour of the STEM subjects – Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths. Other areas such as the Humanities, Arts, and Social Studies are often seen as fluffy, impractical subjects, Friday afternoon fillers in the classroom, even though they’re the keys to critical thinking. And critical thinking is the key to figuring out who we are as individuals, as people, as a society, and what sort of society we want.

When we want to make a little human being, who integrates well into society, a self-aware individual with a clear moral compass, we need to ensure they have the foundational knowledge and beliefs to develop those traits. Unfortunately when it comes to making little human beings, STEM does none of that. At best it helps us with the practical. Science tells us how it happens, Technology helps us achieve it – particularly for those who might otherwise not have children, Engineering builds things that may or may not be useful for raising children (not to mention things that may or may not help us get our kink on in the bedroom), and Maths… well, if that’s your kink, then roll with it. Despite their limitations these subjects are increasingly forming the core of the western world’s curriculum, with the associated implied message: work is the highest aspiration, earning money supersedes morality. Work is life and all else is secondary.

Well I don’t want my kids to grow up like that. Yes, study hard, work hard, get a job; these are things you will need to do. But never at the expense of your values and morals. My children must be able to consider and differentiate between doing some unpleasant work to get things done, and doing unpleasant things to people to get what they want. They need to know where the grey line is and why they should not cross it, and that if they do cross it, why they must then redeem themselves. None of this is covered by STEM.

Shouldn’t schools be working on all of this? Sure, maybe, if they had unlimited resources. That’s why I have to step up as a parent – schools literally cannot do it all. It’s in the simple, everyday routines of families that values are instilled. Do not underestimate the little ritual of reading a bedtime story to your kids, or reading a story together, or, as I like to do, making up a story based on their suggestion. It’s an investment in their literary education – yeah, sure, but it’s way more important than that. Wrapped up in that story is an implied message. It doesn’t matter whether the author has tried to add a moral or not, there is a fundamental moral message in every story.

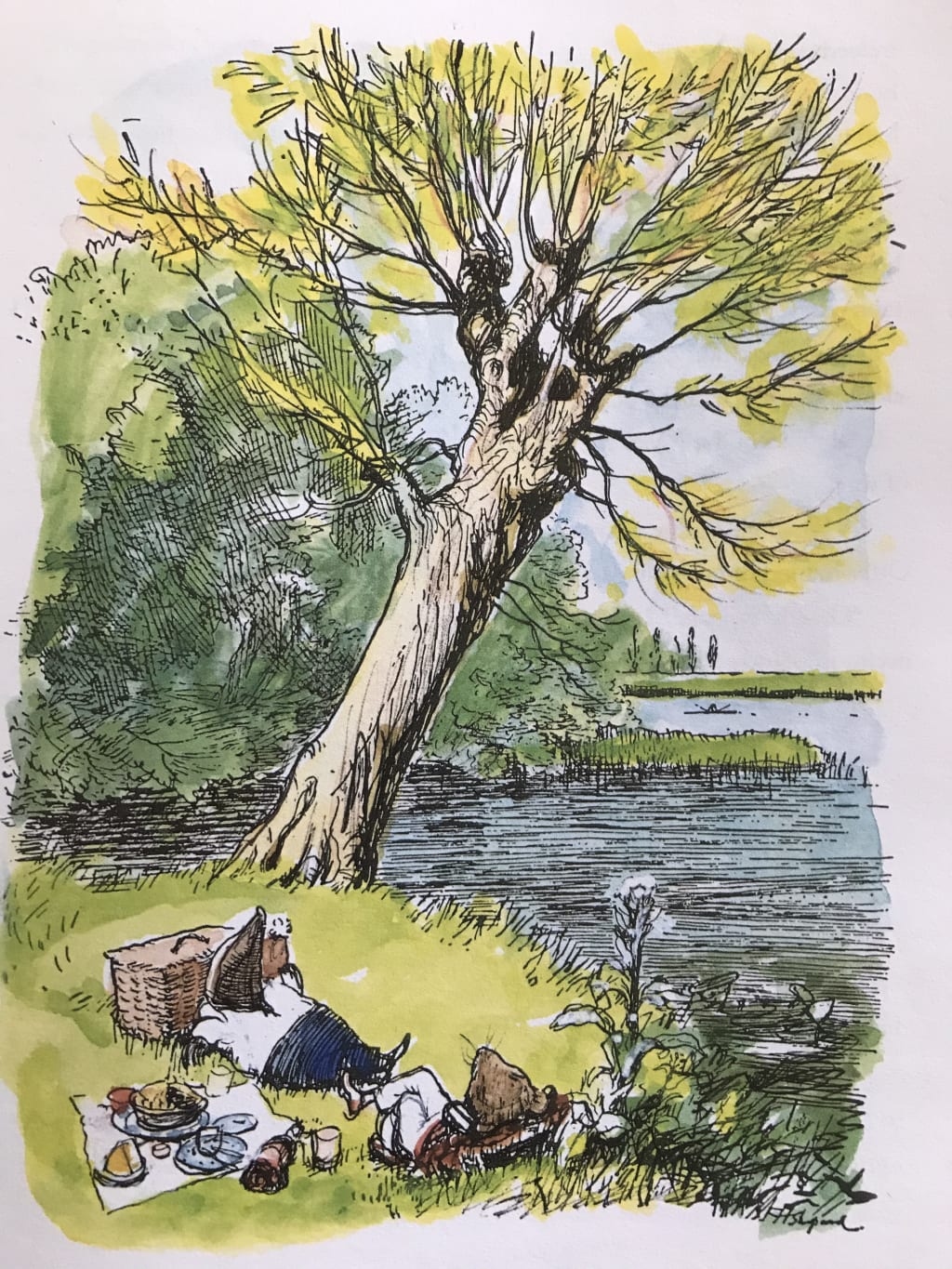

Take as an example one of my favourite books, and one I return to as an adult, The Wind in the Willows. It’s an anthology of short stories woven into a larger poetic narrative. Superficially it’s a story about four English country gentlemen who happen to be animals; a mole, a water rat, a badger, and a toad. Their adventures could easily be described as simple fiction, and generally that’s how they are described by STEM people. But when writing it Kenneth Graham clearly understood each animal’s personality and how it leads each one to act the way he does, often foolishly, or with little regard for others, or simply in arrogant ignorance.

Mole’s occasional hubris causes disaster several times, when he tips the boat over and again when he gets lost in the Wild Wood. Rat’s self-imposed limitations are in conflict with his desire to dream, which almost leads to his abandonment of all he holds dear in the chapter, Wayfarers All. Badger’s reclusiveness leads him to spiral ever inwards, into a musty life of old dressing-gowns, down-at-heel slippers, and self-satiation. And as for Toad, he is simply the embodiment of the unrestrained id. If he feels like it, he does it.

In acting as they do, the animals show us our own very human follies and frailties reflected back at us in story. They demonstrate what it means to act wrongly, to be in the wrong, to err. They also show us the best of humanity, that ability to dream, the fierce love of a place that leads us to fight tooth and nail to protect it, and the willingness for self-sacrifice and hard work to save a friend, even from himself. The stories show characters acknowledging and forgiving each other’s faults and mistakes, and their own: “What a pig I’ve been,” says the Rat in Dulce Domum, when he relises the hurt he’s caused mole.

The actions and consequences experienced by each of the animals throughout the story carries strong social messaging about right and wrong, without ever straying into considering good and evil. This is an important distinction, most of us easily distinguish evil because it tends to be antithetical to freedom and life – there are exceptions of course. Right and wrong are far more fluid and depend on context and are more subject to relative social norms. Consequently they are informed by the stories we tell ourselves about our society, and the bedtime story is happening nearly every night. That is powerful repeated messaging allowing deep thinking.

Right and wrong are subtly nuanced throughout the book, even when it appears very obvious, such as when Toad is being tried for stealing a motor car. Clearly Toad is in the wrong given he did in fact steal a motor car, but the nature of the sentencing is absurdly disproportionate; one year for stealing the motor-car, three years for reckless driving, and fifteen years for cheeking the police, although it was “pretty bad sort of cheek, judging by what we’ve heard from the witness box, even if you only believe one tenth part of what you heard, and I never believe more myself…”. In detailing the sentencing the clerk and wider court display unmitigated cynicism, a complete lack of compassion – even glee in their sentencing, and a severely narrow minded and insular concept of justice. Despite Toad’s being in the wrong, the court are not by default in the right. It is not a simple black and white and therefor demands that people – including young children – think critically about relative morality.

Surely not every bed-time story is as nuanced though. Well, maybe not, The Wind in the Willows has persisted for a reason. So what other books have I been reading to my kids at bed time? A quick browse through the bookshelf yields a wide range of material from their very early years through to when they decided it was no longer cool to have Dad read to them.

Click Clack Moo, D Cronin

Hattie and the Fox, Mem Fox

Wishing Chair, The Magic Far Away Tree, Enid Blyton

Fox in Socks, One Fish Two Fish, etc. Dr Seuss

The Wee Free Men, Terry Pratchett

The Hobbit, Tolkien

Harry Potter (All of them, twice), JK Rowling

The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, CS Lewis

In all of these books the characters act a certain way above and beyond the explicit good and evil. Almost unthinkingly the heroes also act in ways that are inherently right; that defines them as “the good guys” at least as much as their renouncement of evil. For example, Harry Potter is consistently compassionate towards the disempowered, generally honest in his dealings – and when he’s not it backfires almost every time, and he never breaks a promise. In The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, the children are seen to be at their best when they are considerate under stress, remaining thoughtful of others. These are traits we inherently view as both good and right; and they’re traits we are failing to teach elsewhere. Adult literature does not value these traits; someone point to the good guys in A Game of Thrones.

However, as people rightly point out, life is nothing like children’s stories. All of these books are fairy tales, i.e. not real; we don’t have to deal with Smaug, the Queen of the Fairies hasn’t stolen my baby brother, and there isn’t a magic tree that takes me to other lands. “Nothing to see here,” says the STEM adherent, after all there’s nothing concrete to apply to life.

That is precisely what makes these stories so important. They ask us to believe, for a short time, in ideas that cannot exist beyond the story. They demand of us that we believe the unbelievable, intangible truths, that magic is real, that the world is more than it seems, and that right and wrong are almost tangible realities. And most of all, good nearly always triumphs; because those seeking to do and be good will continue to strive to the very end. They will always do what is right, even when it is hard.

Then, when the story’s over, and we return to the mundane world, with its vocational focus and tilt-slab concrete practicality, maybe we’ll bring back some of those intangible qualities with us. Maybe we’ll be able to believe that things like justice and compassion and ethics and aesthetics are important pillars of our society, rather than impediments to our career. And then, maybe, we’ll be able to help build and maintain a genuinely fair and equitable society, something that is bigger than ourselves and our self-interested desires.

Certainly, bedtime stories are not the only requirement to achieve this understanding of right and wrong; there are many factors that go into making a little human being who can think this way. Certainly, there is no guarantee these stories will lead to a strong moral citizen. But equally certainly, without these stories, we are almost guaranteed to fail.

About the Creator

Michael Darvall

Quietly getting on with life and hopefully writing something worth reading occasionally.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.