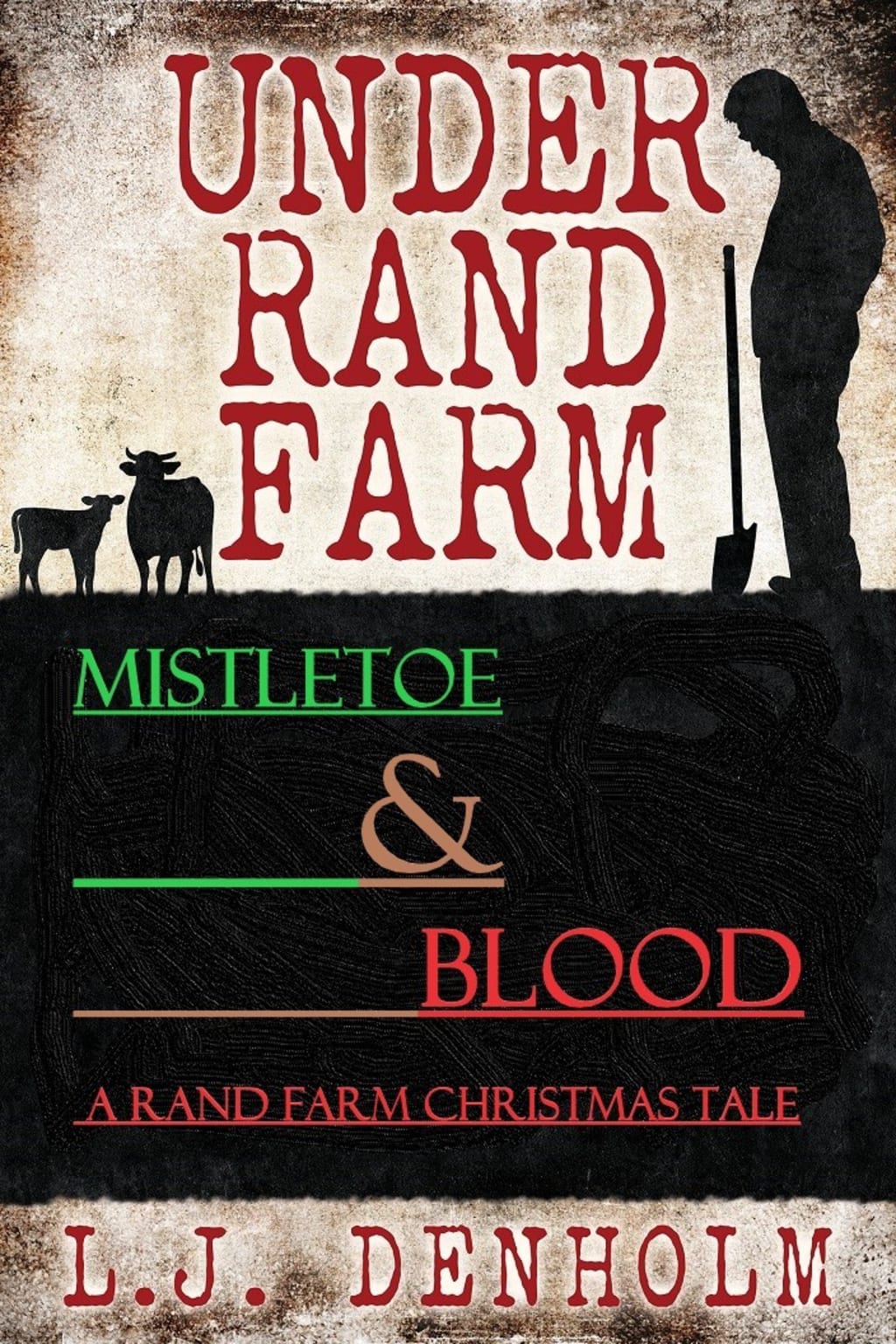

Mistletoe & Blood

an Under Rand Farm Christmas tale

M I S T L E T O E & B L O O D

AN UNDER RAND FARM CHRISTMAS STORY

Two days until Christmas. The mid-90’s. Upstate Pennsylvania.

Patty Rand pulls off the main road and creeps her little Ford toward the RAND FARM arch, wary of the black ice the fierce winter has stamped upon the roads overnight. Grateful for one of the few perks that a farming life has installed in the family mindset: her car is fitted with snow tires. It can just about cope.

Patty and her son, Sullivan Rand, have been shopping at Wal-Mart. The ancient Ford is packed with Christmas food and drink, presents for the family. Sullivan, now fifteen, is sat upfront with her. The weather has crazied somewhat in the couple of hours they have been shopping; a heavy snow shower pelting the area, the air seasoned by the last swirling snowflakes of the deluge.

“Oh,” says Patty as they draw level with a pair of spruces standing sentry either side of the arch. The day before, Patty had decorated the trees – a gift from Lance Newman, an occasional worker on Rand Farm and holder of an unrequited crush on Patty - with a number of plastic decorations she’d picked up from a thrift store over in Lyttondale.

Decorations that have been ripped from the tree by the snarling wind that accompanied the storm. Outsized baubles peek out from the snow. Hooked handles of plastic candy canes peek out from the drift, their red swirls like venomous caterpillars climbing out from the deep white blanket of snow.

Patty flicks a look at Sullivan, who fails to notice both his mother and Even for him, Sullivan has been aloof and distant all morning. Patty suspects teenage hormones are at play; hopes that’s all is up with her son.

Patty is optimistic like that.

“Guess I was hoping against hope they’d stay up, huh,”

From Sullivan, nothing. Patty closes her eyes for a second. Prays that Sullivan and Jack, her fearsome husband, will behave this Christmas. She noses along the track to the house, watched by the rabbits, ravens and the other wild and varied inhabitants that surround the farm’s captive herd of cows, whom Jack has already packed into the great barn for the winter.

Sullivan’s moribund mindset blocks out his mother’s bleating. The day has already seen too much time spent among the blank and empty souls with whom he shares earth, their dumb faces leering towards him as they scramble for the stacked, overpriced goods arranged throughout the hellish supermarket.

He had gazed out of the window as they returned home, watching the empty, endless array of snowy fields, tracked by birds of prey as they seek a sparse, bony meal, and the ruthless corvids waiting to pounce on the bloody remains. As his mother prepared to make the turning to Rand Farm, he considered taking hold of the steering wheel and turning the car into the ditch that runs alongside the road, from which the black vertebrae of fruitless brambles poke out from the snow. There is a certain love and a definite excitement to be found in death, he thinks.

Sullivan has driven the car around the farm plenty when his parents were nowhere to be seen. He enjoyed the invigorating feel of danger that surged through him as he skidded up and down the road, looking for rabbits and chickens to smash.

When his mother begins to simper about the sentry trees, his hand started to twitch toward the wheel. Only then does he see the streak of red winding across the fields, rousing him from the reverie that has befallen him over the last few days, contrasting darkness with angst. Non-venomous yet far bigger, mightier, and deadlier than a caterpillar; has Simon the Serpent, his old friend, come to visit him for Christmas? Sullivan looks over to his mother now, and smiles.

***

Patty pulls the Ford to a stop outside the farmhouse, relieved that Jack’s pick up is nowhere to be seen. Pleased that Sullivan, who now exits the car and is gazing round the fields, looking for Simon, had finally seemed to come alive as they turned under the arch, into Rand Farm’s sixty acres.

Sullivan considers running to the fields to find his friend, before a familial compunction stirs in him, and he helps Patty unload the goods.

After the two have filled the kitchen with the food and gifts, Sullivan dashes upstairs, slipping from room to room in the hope of spotting Simon again; thinking the serpent was slithering towards the arrangement of outhouses that stand plumb opposite the farmhouse’s front door, he starts in his parents’ bedroom, which affords him the best view out that way. Sees nothing but fencing out in the white fields, pockmarked with cow troughs and farm detritus - abandoned or unfixable machinery, rolls of unused fencing, – in danger of being lost to the snow.

After staring around the farm from each upstairs window but failing to spot Simon, Sullivan crashes onto his bed. Simon has abandoned him again. Since the day that Simon started to speak to him, to slither into his room at night and come up with exciting adventures for the two to carry out around the farm:

. . . let’sss catch a chicken . . . bite it till it diesss . . . eat it . . .

Simon has been both a ravenously entertaining companion for Sullivan as he navigated life on the farm – yet unreliable too. Months and sometimes years have gone by between the serpent’s visits.

And now, it seems to Sullivan that the glimpse of Simon is just another flash in the pan. Sullivan clenches his fists, slides them under his long-sleeve black tee. Pulls and twists the skin on his torso.

Downstairs, his mother busies herself in the kitchen. Patty has switched on the radio and is humming happily along to the Springsteen cover of Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town as she puts the Christmas fayre in cupboards. Hoping that this will be a wonderful Christmas time. That Jack will be kind and gentle with her. She is used to his fury; knows much of it is self-directed. Patty wants to help Jack in all the ways she can, yet he remains captive to his anger, which manifests itself physically via his ongoing impotency.

In bed that morning Patty had tried to cajole him along; talking softly to him, touching him, wanting only an open and tactile love in response.

When it ended unresolved, and Jack’s rage returned, she tried to tell him that he needed to get help that reached beyond his flaccidity. To deal with what had passed between Henry and himself under the farm. And he had growled; fought off her love. Left the room. Slammed the door. Driven away, to one of the farmers’ bars that are open all hours, looked for comfort in alcohol and the aggregated disenfranchisement of other members of the farming community.

Patty had stayed in the farmhouse. She is always there, ready to be loved.

She takes a clementine from a brown paper bag, takes in the heavenly scent as she tears its flesh open.

A few feet above her, Sullivan has drawn blood as his thoughts and emotions curdle into a bitter and black liquid that pour into his body, that stain his veins, that further intoxicate his poisoned view of the world,

The snow breaks from the sky, begins to tumble down.

***

JACK RAND RETURNS TO THE FARM later that afternoon, the familiar sound of his pick-up bouncing down the track accompanied by a cacophony of blaring horns and whoops.

He has company. Company he found in a desolate watering hole, company he has now invited onto the farm.

Patty hears the cavalry arriving and switches off the radio. Kills the peaceful Christmas organ music; the gently rousing hymns that have been floating around the kitchen, warming both it and her.

Upstairs, Sullivan is prostrate on his bed, having retreated to a bleak slumber filled with the ghosts of his adventures with Simon. The cacophony of approaching mayhem reminds him of less pleasing memories of the farm.

Jack’s parties.

His father’s farming buddies come round a few nights a year, although usually in the hottest days of summer. They would have a pig to roast and a fire fuelled with the collated wooden ruins of one of Rand Farm’s ensuing series of broken fences.

When they finally left the farm, it was with a wreckage of broken beer bottles, charred meat and pools of urine that somehow overpowered the farm’s own stench of fetid animal waste behind them.

Sullivan returns to his parents’ bedroom, giving him a view of the incoming whoopers. His father is behind the wheel of his pick-up with a man in a red Phillies cap. The face of Tag Burnstock, a drifting farmhand and occasional attender of Jack’s shindigs, blurs into view beneath the cap as the truck approaches. A couple of snow-topped cases of Budweiser are sliding around in the back of Jack’s pick-up. A second truck is coming up from behind, one that Sullivan doesn’t recognise; nor the faces behind the windscreen.

No sign of Carl and Bud – two of Jack’s oldest friends and undoubtedly the most tolerable of the motley network of friends who Jack would occasionally have over.

This absence is a worry to Sullivan. Even though he is a killer – he has murdered his primary school teacher and his maternal grandfather, as well as countless animals around the farm - he craves inner peace and a kind of social tranquillity. For the fantastical voyages of his mind, his heart-poundingly exciting adventures with Simon to play out free from the irksome bother of his enraged father and his cronies, which upsets his mother, too.

This is another unwelcome frustration. Sullivan favours his mother’s company over Jack’s: she is certainly less combustible.

Downstairs, silence and Patty’s hurried footfalls are now abounding in the kitchen. Jack’s pick-up grounds to a halt outside the front of the farmhouse. Sullivan spots a bottle of beer in Tag’s hand whilst Jack’s face is loaded with the alcohol and blood-fuelled ruddiness that Sullivan knows so well. So horribly well. Jack kills the motor then follows Tag in exiting the truck, walking to its tailgate.

The two men who emerge from the second pick-up are certainly many years younger than Jack and Tag, who are making headway into their 40’s. One is a hulking, red-headed man who clambers from the passenger side, while the driver is a slender, pale kind with wiry black hair and narrow, furtive eyes that survey the surrounding farmland, as if working out where its hidden treasures lurk and its exits are situated. Both are equipped with a beer. Sullivan hurries downstairs, calling out to his mother, asking if she is okay. She hums an upbeat response that only confirms that she was not.

Sullivan creeps into the front room as the thickset man from the second pick-up yells out something to Jack, Tag, and the wiry-haired guy as they unload the cases of Bud into a pile. He receives a Sullivan picks out the names Brett and Dave from the stir of macho bawling. Seems Dave is the larger of the two.

Jack, who has not even looked at his own home since returning, looks up at the younger men, smiles aggressively, then winks at Tag, muttering something that has him emitting a laugh squalid as the curtain of dirty-blonde hair creeping out from under his red Phillies cap.

Jack walks towards the second truck, leaving Tag who suddenly turns to the window. It has stopped snowing and the sky is bright and white, backlit by the low winter sun.

Hoping the brightness will make it make it too hard for Tag to spy him, Sullivan steps back a pace. Watches Tag, dressed in a red-black check lumberjack shirt, and filthy, faded Levi’s, squinting his way.

Tag puts his free hand to his brow and picks out Sullivan. Waves slowly upon spotting him. Then he turns as if to join Jack and the others who have congregated by the younger men’s mud-spattered contraption, but suddenly swivels to face the house and shapes to throw the bottle at Sullivan, who throws himself to the floor, waiting to hear the smash of glass upon glass.

Which doesn’t come. Angered that he’s been duped by an asshole like Tag, Sullivan closes his eyes and kicks out at the bear pelt he had dived onto. A fresh volley of guffaws bloom outside the house. Sullivan picks himself up, sees Tag menacingly holding the beer bottle and raising his eyebrows, a shit-eating grin slit across his face. Tag turns to join Jack, who was indulging in a backslapping contest with the younger men. Tag says something, pointing back at the window that elicits another group laugh, which in turn dispenses another round of unnecessarily potent smacks to each other’s backs.

Sullivan sees black, falls back a couple of steps, his heartbeat spasmodic, his thoughts scrambled and chaotic. He manages to right himself by grabbing the arm of Jack’s chair before he could fall to the floor. The blackness in his vision lightens to grey before fizzing out entirely, and he staggers to the kitchen. In here, Patty is hunched over a small wooden table, ashen-faced. Her attention is weakly adhered to making a pie for Christmas day desert.

Sullivan’s throat is bone dry and he struggles to make his voice heard,

“Mom, he’s here, with Tag and some… others.” His mother looked up, her eyes glazed and dulled.

“I heard. Would you go and see if they want some food? Your father’s had a long, hard year and he needs to let off a little steam with his friends.”

With that, Patty smiles curtly and returns to peeling a mound of sweet potatoes.

Sullivan’s feels his blood boil. His mother’s defeatism at the hand of Jack’s endless cruelty pierced through his skin and eyes and bursts his soul, augmented by Simon’s ongoing absence from his life, by the cruelty of thinking Simon had returned earlier in the day, sending black shrapnel billowing through his body, like confetti at a demon’s wedding.

“No. No. No! You fucking weak, fucking pathetic, fucking bitch!” roars Sullivan, his hands hot and his voice deep and guttural, barely his anymore.

His mother looked up in abject fear at her son, the first time that she had looked at him with anything other than hope and love, however futile these things are. Sullivan crashes a fist onto the table. Several clementine spill from a fruit bowl, roll around the table in wobbling arcs.

Sullivan stands back and stares at his mother, snorting breath in and out through his nose like an enraged buffalo, his pupils dilated to the point where his irises have disappeared, consumed by their darkness. His mother cowers in silence, her mouth gaping as her son looms over her with violent intentions.

Sullivan raises his arm, his fist shaking with fury. The black shrapnel still falling through his body; lethal, jagged shards of dark matter stabbing into his insides, charging his body with a possessive, febrile energy.

He slams his fist down upon the table once again, making his mother jump up, screaming. Several more clementine spin onto the floor. Sullivan continues, deals a mighty kick to the underside of the table, yielding a cracking sound that he feels jarring through the bones of his right foot. The fruit bowl slides off the table and smashes. This gives a temporary pause to the raw, wild energy flowing through his body and he stands seething, surveying the mess of fruit and the shattered fruit bowl on the floor and his mother, holding onto the table, tears streaming down her face.

Sullivan moved to his mother and feels a swell of humanity wash through him. He embraces her for a moment before turning to exit the kitchen.

“Sully, where are you . . .”

His mother’s question dies in the water as Sullivan turns to her, the blackness returned to his eyes. He walks over to the knife-block, snarling when almost slipping on a spilt mush of clementine on the way. He pulls each handle in turn from the block, inspects the length and sharpness of each blade, settles on a medium chopping knife which pricked the end of his index finger with ease. Satisfied, he storms to the back door, turns the key that lives in its lock. Pockets the key. His mother gasps as he exits the kitchen, heads outside, locks the front door and moves towards the cat-calling and the whooping. Towards his father.

Armed with a knife.

***

Sullivan stumbles as he marches into the snow-topped, icy clearing outside the great barn, the largest of the farm’s outhouses. Sees Jack and the younger men, inspecting a bunch of pallets piled up near the end of the barn. Hurries toward them, the aching in his foot contained by his rage.

His focus on his father is such that he doesn’t spot Tag, leant up by the barn’s side door with one foot rested on a crate of beers plugged into a small snowdrift beside him. Tag’s smoking a rolled-up cigarette. His eyes are glazed and shadowy under the rim of his cap. He pushes himself away from the barn, ambles into Sullivan’s pathway to Jack.

“Well, what we got here, boys…” slurs Tag, loudly enough for the others to look up, see Sullivan and walk towards him.

Sullivan snarls, “fuck you, Tag” tries to push past the man, the knife’s handle in his fist; its blade concealed up his sleeve.

“Woah!” says Tag, sticking out a desert-booted foot, sending Sullivan sprawling to the floor, and his knife dancing across the clearing, sinking into the layer of snow that glazes the yard.

Sullivan tries to scramble to his feet as his dark energy dissipates; instead the familiar sting of humiliation is taking its place, spreading like a rash over his body. A heavy boot steps on his back. Subdues his efforts.

“You doing out here, boy?” Jack, the boot’s wearer, asks Sullivan in a hoarse hurricane of a voice.

Sullivan trembles as several voices snicker around him. Obsequious laughs that cling to Jack like parasitic fish to a shark. He wants Simon to emerge. To augment his hate.

“You doing out here with a knife, more to the point…” Jack took his boot off his son’s back, moves to the fresh hole in the snow, stoops, picks up the knife by its handle, which he turns round and round, inspecting the blade with interest. Pauses, trains his eyes onto Sullivan.

“Hmmm… guess you came to give your old man something to cut the turkey with on Christmas Day, huh boy?”

The small crowd draws silent around Sullivan; then giggle and snicker again as he manages a meek “yessir” in response.

Jack grunts. “Well, that’s mighty good of you, boy. Mighty good. Course, all the folks here know just how fuckin’ excited a little boy gets at Christmas time!”

Jack’s throat crackles with laughter at his own half-joke. One that the others echo with dirty chuckles of their own.

Sullivan sits himself up, crawls to a nearby haystack. Collapses his back up against it.

“Well, thank you boy. For my early present of this sharp, sharp knife.” Jack runs his finger along its blade, drawing a blob of blood at which he stares with mock curiosity as it courses down to the palm of his hand.

“Ooh-ee! Any harder and I could have lost me one of these delicate little pinkies of mine and wouldn’t that be a damned shame! Because I think I’ll be needing these for all the fuckin’ presents I need to wrap up for you and your mother!”

Tag and Brett snicker; Tag’s is particularly acidic. Dave has paled and lost his smile. Looks overawed by the direction of the afternoon.

Jack glares at Tag once again, then regards his son, slumped against the haystack.

“Get to your fucking feet, boy,” Jack snarls. “Why don’t you ask your mother if she could rustle up a little Christmas treat for me and the boys.”

Tag guns a sick laugh, saying, “Something like blowjobs all around, huh Jackie-boy?”

Jack pauses his knife-play, fires a dark look at Tag. “Yeah, something like that, Tag. Taggy-boy,” he adds, in mocking tones.

Sullivan pulls himself up to his feet. Hopes – and fears - that Tag has pushed Jack too far: Jack’s sexual frustration is not lost on him. Jack has slammed a thousand doors, has shouted a thousand obscenities, loudly blamed Patty a thousand times for his impotence, usually with Sullivan stewing darkly a few feet away in his bedroom.

Jack grunts, then points at Dave and Brett. “Boys, why don’t you go fetch some oil drums from around the back. No one’ll have anything worth blowing in this fuckin’ cold.”

The two glance at one another then slink off to fetch the drums. Emasculated by Jack’s derision, Tag skulks away to fetch the cases of beer, staring hard at Sullivan as he leaves.

Jack attempts a little edification with his son. “Don’t worry boy, the only thing being blown off out here today is a little steam. Tag’s full of shit. C’mon, stick out here a while. Have a drink with your old man.”

Brett and Dave return into view, dragging a couple of oil drums each. “Set them set them around the sides, see,” orders Jack, pointing at the edge of the great barn. The pair busy themselves breaking up some pallets piled up against the side.

Tag returns, dumps the beer crate by the barn door. He hands the beers around, pausing when he gets to Sullivan. He narrows his eyes, calls over to Jack, “Your boy good to drink?” Spits while he talks.

Jack furrows his brow. Finally quits toying with the knife, slips it under his belt. “Well, let’s think about this. Hmm. He’s a Rand, aint he? And it’s Christmas, aint it? So yeah, give the boy a fuckin’ beer, Taggy-boy.”

Brett and Dave laugh softly, uneasily, caught between the volatile nature of Jack, and the back-stabbing, untrustworthy weasel that is Tag.

“Sure thing, Jack,” answers Tag, arrowing a loaded glare at the two. Set on establishing himself as second-in-command of this little troop, he looks deep into Sullivan’s eyes as he hands him a beer, once again feinting to throw the bottle at him. Sullivan foresees this attempt; rides it out. All the while managing to maintain eye contact with Tag. Jack sees Sullivan’s fortitude and a hint of a smile creeps across his face. It is rare for the Rand men to share warmth and the hot black coals of both Jack and Sullivan’s internal fires momentarily glow with bright hot orange cracks.

Tag drops his stare. Kicks the snow.

All now have a beer on the go. Brett and Dave attempt to weigh in on the day, spinning a yarn about a show they’d seen the night before at a strip joint -“Man, that elf had the biggest pair of titties I ever did see on a fucking, Christmas goblin,” - spits Dave, his goofy grin returning as Brett eggs him on, happy for his dim-witted friend’s story to raise himself at least above Dave in the male order of things.

“She draped a booby on me when I slipped her that five buck bill, y’see that, Brett?” asks Dave.

Brett rolls his ratty little eyes. “Yeah, she was so close to giving you a free handie cos you’re just so charming and handsome and generous with your money.”

Dave grins, gurns. “Yeah, yeah, laugh it up, but I took myself a souvenir . . .”

The big man feels in his back pocket, pulls out a green mush of something. Holds it up to those around him.

“The fuck is that, boy?” asks Jack.

Dave smirks with unmerited confidence.

“Mistletoe. Bunches of it were tied up round the poles, y’see? Gonna go back there at new year’s, hook it around my belt buckle.”

Jack chuckles slowly, Brett barks a laugh. Tag is still soured by Jack’s emasculation and his freakish boy’s weird, horrible stare. He stashes his grudge for the time being, hides it with a generic guffaw at the stripper story, then asks,

“And you think that little piece of vegetation’s gonna get you blown, fella?”

“Nope,” says Dave. “Gonna tuck a ten dollar bill in there too.”

Five minutes later the men are still hooting with laughter at Dave, who seems happy enough to be causing the uproar and keeping events knife and anger free. Sullivan enjoys watching the men laugh; their segue from anger and machismo to freeform laughter fascinates him.

Jack slaps Dave, sending his spoiled mistletoe sprig from his hand and becomes the latest item to be taken by the snow.

“You’re kidding yourself there, big fella. But I’ll toast to that story. Fresh beers needed. Tag!”

Tag mumbles, but stalks off to grab a fresh round of beers. Jack’s taunting of him still rankles; as does Sullivan’s unexpected bravado. Tag wants revenge on at least one of the Rands. Will bide his time. He kneels into the impromptu, snowdrift beer-cooler, pulls out another five bottles.

The sun recedes, taking its low wattage rays with it. Jack notices big Dave shaking.

“Christ, colder than a Canadian cooch out here,” Jack says, He sets the knife on top of a broken wheelbarrow, tasks Brett with fetching a sledgehammer from the tool shed and Dave to line up the pallets. They jump into the task, whooping as the pallets splinter and break apart. Tag loads the broken wood into the oil drums as Jack hunts for fuel in the tractor shed. He returns with a jerry can of diesel and sloshes the accelerant into the oil drums, also pouring some onto Dave’s shoes, as he returns red-faced from his pallet pounding. This makes everyone – except Sullivan - laugh; Dave’s honking guffaws louder than anyone else. Tag’s are forced; stained.

Tag throws his lighter over to Jack who pours fuel onto the end of an pallet slat offcut, lights it, and dunks it inside each drum, a round of yeahs and whoops greeting the resulting flames that leapt into the chill winter air.

The afternoon wears on into evening, darkness arriving between the two. More beers are sunk. Sullivan is on his third and has had to go piss twice behind the barn already, drawing catcalls from the others. The banter remains base; tits, beers, other farmers who are in sore need of a punch. Sullivan learns that Brett and Dave are – as he had already assumed – farmhands of no fixed employment.

Sullivan’s bladder is squealing, and he has to go. A decision made definite when Jack starts an acapella, atonal version of Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town with his new friends as Tag lurks on the periphery of things, stalking the farmyard perimeter, smoking cigarettes and sucking back beers at a rate somewhat slower than Jack and the others.

Sullivan’s head starts to spin. He looks over to the farmhouse, up at his parents’ bedroom window, where a light shines, a beacon to his home, where his mother has remained, alone, basking in her own defeatism.

He laughs coldly, makes his way behind the great barn.

***

It has been a long and hellish time for Patty since Sullivan stormed out of the house, armed with a knife. After the initial shock she sped upstairs and used the key that Jack doesn’t know she has had made, opened up his gun closet and taken a rifle. Her heart pounded as she shouldered her weapon and hurried out to the clearing.

When Patty saw Jack’s foot upon her Sully’s back she tried to yell but the words lodged in her throat like fishhooks. Fear constricted her legs and she stood, useless, able only to watch. Only fifty yards away but no one looked up and saw her, so transfixed were they on the unfolding scene. In better news she couldn’t see the knife in her son nor her husband’s grasp; nor had the other men grabbed it. She hoped it had been lost to the snow.

It seemed that Jack was trying only to subdue Sully. This eased her rigidity somewhat and she managed to lock and load, and with a shaking hand, draw Jack into her sights . . . wanting to be sure that should things worsen, she had a clear shot.

Once Jack had taken his boot off Sullivan, found the knife, and placed it out of harm’s way she crept round to the rear of the feed-house, ducked down and resumed her aim towards Jack. Things calmed and although the subject matter made her rolls her eyes, she felt awash with relief when the talk turned to the usual stalwarts of farmers’ braggadocio – guns, strippers, ripping into their local farming rivals. That Sullivan was drinking was a mild concern – the limited experience her son had with alcohol (that she knew of) was of an occasional beer at Jack’s barbecues. Of vomiting after.

She also believed that Sullivan was safe from Jack, who for all his rage had not yet become violent against him or herself, venting his rage on the farmhouse’s walls and various inanimate objects. Patty decided she would watch for as long as she could – she was shivering with her feet soaked through. In the course of fetching the gun and dashing from the house she had not had time to pull on a coat, and she has nothing more on her feet than soaked woollen slippers.

As the light fails, the men – and Sullivan - are continuing to drink. Patty watches, waits, the gun a trigger-pull away from blasting someone to death. The men start to sing. Sullivan looks over to the farmhouse, Patty silently implores him to wander back home.

As Sullivan heads behind the barn in a drunken, zig-zag of a gait, she bows her head. Then moves to the far side of the feedhouse, waits for her son to emerge fifty yards away from her, but with Jack out of sight. She can call out to Sullivan, or simply walk over to him.

***

Tag needs to piss. He is tempted to follow Sullivan when the little rat goes off to empty his pissy little girl’s bladder round the back of the barn, give him a bit of a hiding. But he fears Jack too much; even though he believes Jack is like a male lion – capable of killing and devouring his own blood, should his hunger direct him so, should anyone else try and take the boy down a peg or two they’re likely to meet Jack’s ire at its most furious. He has had enough of this shitty farm, of the shitty life he leads, working all day just so he can pour cheap beer down his throat.

Tag deserves something more. Something that Jack and the young halfwits sucking up to him can’t offer.

A Christmas present.

Tag holds on, sinks his beer, only stretching his bladder the more. Whatever the kid’s doing, he’s taking his time. Tag considers going into the barn, past Jack’s haggard cattle who he can hear low weakly in their filthy pens, and pissing all over the floor of Jack’s excuse for an office down the back of the great barn. Maybe there’s a coffee cup of Jack’s he can slosh into.

The thought makes him smile but he’ll need to keep biding his time. He drains the rest of his beer and belches. Jack, Dave, and Brett are starting a singalong; that fucking Springsteen song. Tag looks around the decaying little farm, thinks that no way is Santa venturing away from the town to visit this shitheap. Fed up with waiting for Sullivan to return, Tag drops his empty bottle into the snow and walks away from the fire and the drunkards, into the darkness.

Spots the glint of Patty’s rifle as he goes.

Tag changes tact. Sneaks to the broken wheelbarrow and swipes the knife. Changes his direction.

Christmas may just be coming early.

***

Patty waits for her son to stagger from behind the barn out into the fields, the bitter cold shaking through her bones which it finds easily underneath her lean, taut frame. When he emerges she will walk directly to him, will call out his name evenly. Not too loud – although the men’s singing is now so rhythmless that the distressed lowing of the cattle is more tightly harmonised.

Sullivan finally comes into view – he is walking whilst pissing. Patty closes her eyes.

A hand covers her face.

Sweaty, clammy, granulated with dirt and reeking of cheap tobacco. Patty fights immediately; she goes to swing her gun but before she can build the necessary momentum she is face down in the snow, tasting the earth beneath. Her gun falls from her grip.

A knee is on her back, and being pressed down with such pressure she has to splay her limbs out. She tries to wriggle free until she feels the cold, hard blade of a knife on the back of her neck. Warm breath rushes against her ear, the sour tang of beer and tobaccos chases it.

“Shhhh,” whispers Tag. “No need to worry, Patty. I just came for my Christmas kiss.” Something is tickling Patty’s forehead. She swivels her eyeballs up as far as she can. A desolate sprig of mistletoe is bobbing around her face.

Tag grinds his knee up Patty’s back, hard and slow, until his bony kneecap is arrowing into the back of her neck. Her face grinds in a pudding of snow, mud, and urine-soaked hay. He grabs the rifle and chucks it behind him.

“Pretty lady like you need a gun for, huh? I saw ya holding it up when Jacky-boy had your spooky little kid face down in the snow. Kinda like I have with you now, huh.”

Patty manages to squirm her head round enough to spit at Tag,

“Jack’ll beat the shit out of . . .”

Tag cackles. “For what? I’m just after a little kiss, sweetheart. Nothin’ more. Old Jack looks like he’s got himself some new blood to blow him, anyway. Fucker walks and talks like he’s Billy the Kid, but I think he’s soft as shit, when it comes down to it. Bet he aint fucked you since that little freak fell from your snatch.”

Patty tries to scream out. Tag jams his hand around her mouth.

“Naw, you keep quiet sweetheart. Is gonna be as big a treat for you as it is for me, I promise you that. Now let’s get us a little privacy. And don’t even think about screaming or running off, or I’ll be the first fucker round here to have the balls to use this . . .”

Patty sucks in a gasp as her kitchen knife is ran across her throat.

Tag hauls her to her feet, pushes her into the feed-store. Slams the door shut, turns the key that dumb Jack has left in the door. Tag then takes a short walk to scope the area for spoilsports. Jack’s laughter is still raucous, roaring above the obsequious gales of hilarity that Brett and Dave are engineering. No sign of the boy. Tag turns, heads for the feed-store, ready for his Christmas present.

Tag is smashed around the head. He pirouettes, sees a diminutive, colourless figure looking at him. Tag swipes the knife at his assailant, missing by a country mile. His eye sockets fills with blood from the attack. He gropes to prise the blood away, which regains him a blurred degree of sight. The figure is gone. A white-hot pain sears into his buttock. Tag spins around, too slow to stop the administration of 5mL of ketamine into his ass.

Sullivan cracks Tag across the lower back once again. He buckles, falls face-first into the snow. Sullivan drags him into the cellar. Locks the door behind him, jogs upstairs and outside and takes the knife from the snow. Ambles to the feed-store, unlocks the door and steps back as Patty swings an ancient broom at him.

“Oh, Sully, I thought you were . . .”

“Tag? Don’t worry, mom. Dad saw him off. Think he had gotten a bit outta control. He’s running up out of here now.”

Patty has her hand to her heart. “Jack . . . Your father did that? He got rid of Tag?”

“Yeah, sure, mom. He snuck up here and grabbed Tag and marched him up the road. Tag looked terrified. Guess he’ll have to hitch back to Lyttondale.”

Patty thinks. “I heard nothing . . . where is your father now?”

Sullivan looks up and away for a beat. “Think he’s gone to send the others packing.”

Patty manages a small laugh. “Well. That’s . . . considerate. But irresponsible. Them boys can’t be in any fit state to drive.

“Tell your father that I’ll run them back, later. And if they want anything to eat. I bought a silly amount of food today, may as well get some of it eaten tonight.”

Sullivan grins. “Sure, mom.”

Patty finds the rifle, scurries along back to the farmhouse. Sullivan goes back to the great barn where his father is moving towards being unable to stand due to the prodigious amount of alcohol he has taken. The boys are not faring any better. The absence of Tag is lost on the three.

After Sullivan spotted Tag leading his mother into the feed-house, his dirty paw clamped over his mouth, Sullivan foresaw red. Tag’s blood would have to be broken out of his veins. Only he is allowed to end his mother’s life, her suffering.

. . . Let’sss make him pay . . ., Simon the Serpent had whissspered to him, as he slithered into view, at last. Sullivan felt a kind of love wash through his own veins and bones, snuck into the great barn – not even registering in the drunkards peripheral vision – and took a rusty, disused branding iron, hooked a bunch of cow straps around his frame, as well as a drawing up a juicy shot of ketamine from an old vial that had sat around for so long he wondered if it retained any kind of potency: Jack had long since bought it from an unreputable vet. Sullivan had seen its effect on cows, and on Jack himself.

After subduing Tag, and tying him up in the cellar, Sullivan returned to his drunken father and his friends.

“Well, the progida . . . prodigal son returns,” slurs Jack. “Hey. Hey! ‘The fuck has Tag, Taggy-boy gotten to?”

“Said something about going on over to that strip club?” Sullivan said. “Said he’d hitch back to Lyttondale.”

Jack snarls, “Yeah? Well fuck him, then. Whaddya say, boys? A toast, ‘fuck you, Tag,’ sound good to you?”

The three look at one another, before launching into a fog-horned, bellowing, “FUCK YOU, TAG!”

“Your mother, what she up to?” asks Jack, looking uncharacteristically sheepish.

“Ah,, she’s fine, dad. Fact, she asked if you wanted some food bringing out . . .”

Sullivan walks back to the house, peels some potatoes for his mother to make spiced wedges with, to go with the huge batch of sausages she is frying up. When all is cooked, Patty and Sullivan take them to the yard along with cutlery. Jack thanks the both of them.

An hour after the men have eaten and Patty is driving Brett and Dave home and Jack has come inside and is snoring, foghorn loud on the sofa, Sullivan takes a stroll across the yard to the cellar, turning the knife handle in his hand. Simon slithering alongside him. Lets himself into the cellar.

Works on Tag’s face with the knife and his – and Simon’s – teeth, until he hears the old Ford crawling back to the farmhouse. He slips from the cellar, sneaks back into the house, crawls into his bed.

It was going to be a fine Christmas for Sullivan Rand.

***

Tag wakes, shivering rabidly, his head constricted by something clothlike that prevents him from opening his eyes. His whole body spins with nausea. He tries to move but his arms can’t move from his sides, and his legs are tightly wrapped against one another. While all of him is sore; his face pulses with a particular kind of agony.

He tries to yell out but he gargles his words. Can’t get them past his tongue. He tries to scream but he can’t feel his lips. His face is frozen with pain and terror. His breath becomes rapid, his heart thumps and races. He tries to calm himself.

He hears a sound. Hisssss . . .

He yells now, a shapeless sound that rebounds off stone walls and floor and ceiling of the cellar, reverberates weakly, sharply dies in the freezing air.

“Wha . . . who tha . . .” croaks Tag, the numbness of his lips and tongue making him lisp.

“Ja’. Jaa. Jack. Tha you? Mithundersthanding wi’ Patty.”

Tag tries to sound strong. Fails. The darkness leers at him, its swirling black and grey dots pour over him like a dead ocean.

“Ja’? Ja’?”

A beam of white torchlight spears into his eyes. He swallows a scream. A diminutive silhouette stands behind the source of the light.

“Thullivan . . . Thully? Ah can you help me?”

The silhouette takes a few laboured steps towards Tag, stoops down and places a photo frame a foot from his face, propping it up with its stand.

“Wha . . . wha . . . wha thith?”

A whisper in response. “Who do you sss . . . see?”

Tag releases a captive choking sound.

“Wha . . .” Turns his eyes to the photo, squints against the irrepressible light that bores through the terrible darkness. Trapped in the frame is a pale face covered in birthmarks that leers out at him. Its lips look like they’ve been lost to scurvy. He gasps.

As does the mirror in the frame.

Another whisper. “Thanksss for the meal,”

Tag is crying. The light wavers, illuminating his body. He looks down to see he is wrapped up with a multitude of cattle tethers, the cheap and worn kind that Jack Rand has had hanging up at the back of the great barn since forever.

“And thanksss for the kisssss . . .”

The silhouette leers towards Tag. Spits the end of his tongue into his mouth. Tag defies his ragged lips and stump of a tongue, screams loud and free as the silhouette dangles the mistletoe in his eyes, then scrunches it into his mouth, squeezes his cheeks shut and screams at him to eat and swallow his own tongue.

Tag complies, watching strings of bright red blood wind down from the white chin of his tormenter who screams with humourless laughter as Tag feels his tongue stick in his throat.

***

The next morning is Christmas Eve. While Jack and Patty spend a fruitful morning in bed, Sullivan lets himself into the cellar, tethering a winch rope to Tag’s leather restraints, hooking it to the back of the old Ford, heaving his drugged, mutilated, being from its terrible depths. Bundling him onto the backseat of Patty’s Ford, doing the injured man the favour of driving him home.

Of helping him into his apartment.

Of whispering what would be in store for Tag next if he lived to see another day. Of leaving him a mirror to gape into and admire the remains of his face. Of leaving him his rifle and a bullet.

Of calling an ambulance and aping Tag’s voice, asking for the paramedics to collect a dead body from Tag’s one bed apartment in the side streets of Lyttondale. Suicide by a massive, self-inflicted gunshot wound to the face is the coroner’s finding.

But Sullivan doesn’t care about this. He has the whole of Christmas to look forward to, with his old friend by his side.

***

IF YOU ENJOYED MISTLETOE & BLOOD, you can read the full length novel "Under Rand Farm" available on paperback and Kindle now - it's FREE on Kindle Unlimited - and a Christmas '21 Special Edition is out now that includes Mistletoe & Blood!

LJ Denholm is a pseudonym of the humour writer JS Harding.

You can catch up with my latest writing news at www.jsharding.com, or follow me on Twitter: @JSHaHarding and @LjDenholm

I love you. Bye!

About the Creator

jamie harding

Novelist (writing as LJ Denholm) - Under Rand Farm - available in paperback via Amazon and *FREE* via Kindle Unlimited!

Short story writer - Mr. Threadbare, Farmer Young et al

Humour writer - NewsThump, BBC Comedy.

Kids' writer - TBC!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.