Were the Pyramids Built from the Top Down?

The surprisingly simple idea we haven't considered

I promise I'm not going to suggest the Pyramids of Giza were built by aliens.

Instead, I hope to outline a simple act of engineering that could have been used to construct them.

The idea came as I was putting away the dishes. The bowls in the cupboard are stacked to save space, nested within each other, with the smaller bowls on top, the larger on the bottom. As I slid a shallow ceramic dish beneath the stack of white bowls, something clicked.

What if that had been used as a building technique of the past? Slipping one stone beneath the other, tightly fitting it within its neighboring building blocks. What if the pyramids were built not from the ground up but from the top down?

I invite you to suspend your disbelief for one moment and imagine the following scenario:

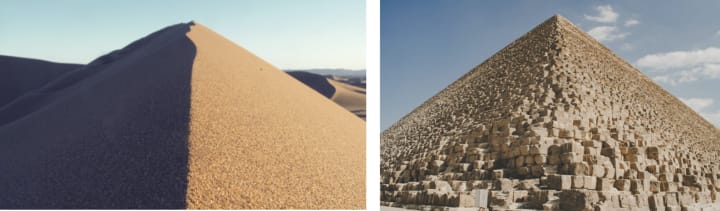

A great sand dune exists. One that is hundreds of meters high, like those that can still be found in parts of the Sahara Desert.

Now imagine you are an ancient architect. You see this sand dune as an opportunity, a natural template and scaffold by which to guide the design of one of the most important structures ever attempted: A great pyramid.

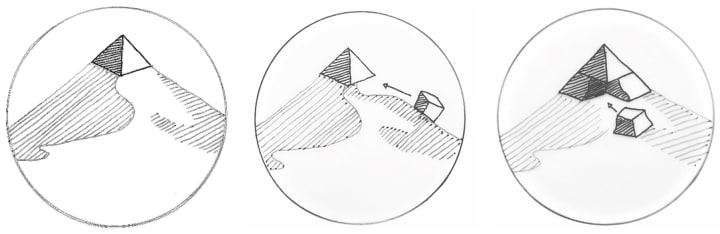

You start with the cap stone, enlisting the help of a dedicated team to assist in hauling the multi-ton stone up to the top of the sand dune. Water is used to make the sand slick and compact it to form a path up the natural slope of the dune.

At the top of the dune, you work diligently to position the capstone in place. This is the most crucial part of the whole design because it sets the baseline for every layer beneath it, so you take your time surveying, measuring, making sure it aligns with your vision—and with the stars.

Now imagine that you and your team excavate the sand beneath one corner of that capstone. The majority of the immense weight of the stone is still being supported by the dense sand underneath. Into that hole, you slide another stone. Then, ensuring the capstone remains supported, you strategically excavate more sand away and slide in another stone.

The team’s expert masons chip away at these stones, adjusting them, ensuring that they don’t just fit together well, but nest within each other perfectly like puzzle pieces. This a key aspect of the build, as it will help the layers maintain their stability throughout the construction process. The massive, tightly-knit stones will help to reinforce one another, allowing sections to be excavated underneath, strategically supported using sand and any additional bracing required as construction continues beneath.

Row after row, you and your team continue this pattern, excavating and sliding and fitting in multi-ton blocks, displacing the massive volumes of sand, slowly but surely replacing it with limestone.

As you move downward, the structure grows in scale. Work begins on smaller, adjacent pyramids and soon it is all hands on deck. More and more workers are needed for the operation—for shoveling and redirecting sand, mining the quarry, cutting and hauling blocks. Others work to polish the outer stones so that they gleam white like a shining beacon atop a mountain of sand.

It is backbreaking work under the hot sun, but every night from your home, you watch the light of the setting sun reflect against the shining limestone and you feel proud. One day, you will build down far enough to reach the bedrock of the plateau and lay the final row of blocks. One day, the entire dune will be levelled, and what will remain will be a series of permanent structures rising up from the sand, each lasting an eternity.

Of course, all of this is hypothetical: no one truly knows how the pyramids were constructed. But maybe we can gather clues from other examples of engineering throughout history.

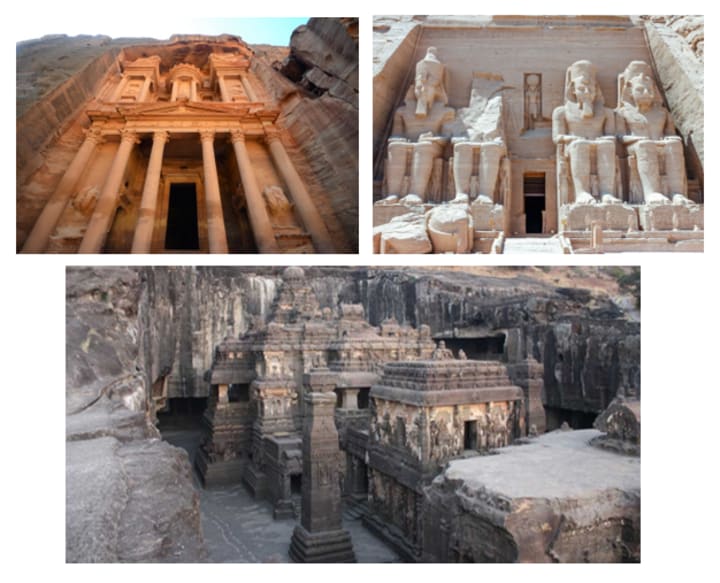

As it turns out, there are many ancient wonders constructed from geological formations that existed there naturally. Rock-cut architecture, for instance, is a technique that involves forming structures in place from naturally occurring solid rock that is already present at the site.

In most cases, this involved a type of vertical excavation, with workers beginning at the top of a giant existing rock formation and working downward, carving out the structure.

The Great Temple of Abu Simbel in Egypt, Al Khazneh at Petra in Jordan, and the Kailasa Temple in Maharashtra, India, are all examples of rock-cut architecture built from the top down.

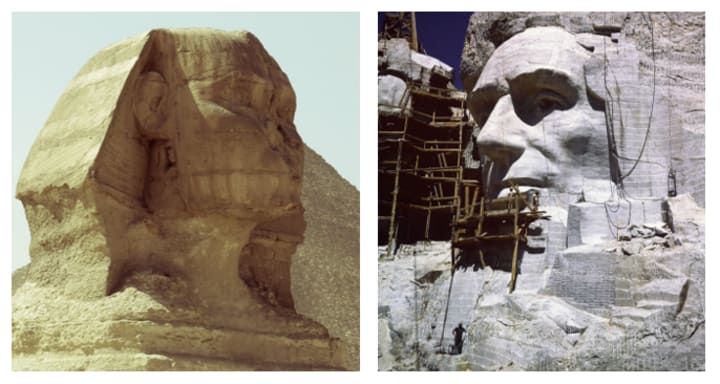

The Great Sphynx—the giant human-lion hybrid that sits at the base of the Great Pyramid—is also said to be constructed using this method. As was Mount Rushmore.

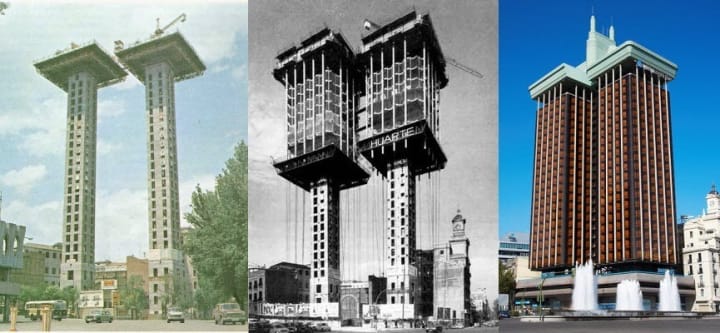

But top-down engineering is not just limited to structures built from existing geological formations. It is commonly employed as a modern construction method when a building project involves deep excavations or site constraints. It can also be used as a time (and money) saving strategy, as it can allow for simultaneous work to take place in the below-grade substructure at the same time as the higher levels of the superstructure.

In top-down construction of high-rise buildings, a permanent internal structure is created that temporarily acts as the project’s main support system, bearing the load as levels are added in sequence from the top downward until the lower retaining walls are built and connect in with the foundation.

Underground projects such as car parks and subway stations often employ this technique to limit interruptions to traffic and other activities at grade, and in cases where soil movement needs to be minimized.

In this type of excavation, the use of retaining walls and steel piles are constructed, and a concrete slab is cast in place. Then, the soil beneath the slab is removed from underneath the slab to create lower basement levels, casting additional sublevel floors, and excavating below those as needed.

As long the elements being constructed are properly supported (even if those supports are temporary) it is possible to begin at the top and build down.

Which brings us back to the Pyramids of Giza.

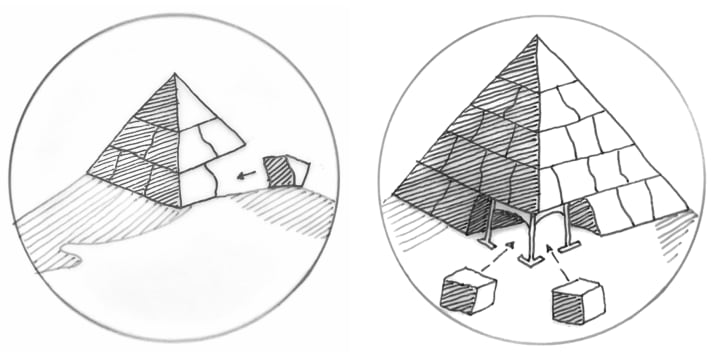

If the upper sections of stone were adequately supported by sand and additional bracing techniques where needed, this could allow for controlled access to small sections of the underside at a time, allowing lower rows of stone to be added in sequentially.

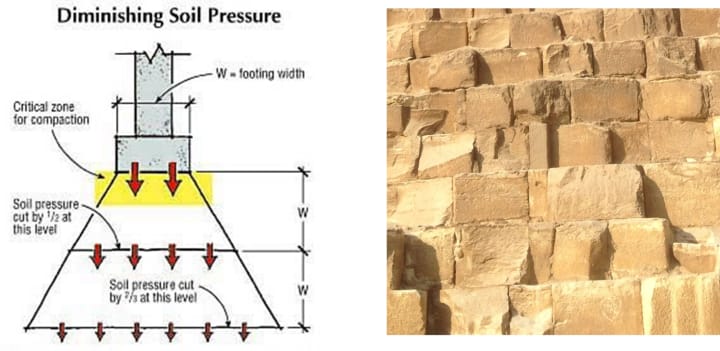

If you’ve ever climbed a sand dune or laid a foundation for a patio of pavers, you’ll know that sand can support a lot of weight due to its density. Sand has the ability to bear the weight of 3,000 pounds per square foot.

The stones in the pyramids vary in scale, but the majority are estimated to have a footprint of about 3 by 4 feet, and weigh about 2.5 tons (approx. 5500 pounds) each, meaning that a layer of sand even one foot deep would be able to support the weight of a row of these stones.

However, if a dune really was used as a temporary foundation, it would have meant that sand would have been more than just a foot deep, just as the stones would have been layered to be many rows in height. The trick to carrying the huge load might lie how the pressure from a load is dispersed through the soil. At each point of pressure, the load from the above structure would be transferred down into the sand, spreading out at an angle and decreasing in pressure as it moves downward.

The shape of the dune would accommodate this principle well as it is already naturally angled for maximum stability.

Also, because the stones were fit together with such high precision—some joint openings are said to be less than 1/50th of an inch wide—this might have granted each layer additional stability, with blocks locking together like a raft on sand, evenly distributing the load.

Then, like an a ancient game of Jenga, small areas of supporting sand could be strategically pulled away without compromising structural integrity, creating voids where stones could be methodically slid into place beneath the previous layers of stone, repeating this pattern until completion.

Currently, there is no universal consensus when it comes to how these enormous structures were constructed. New possibilities are always worth considering, and what we think we know is always worth questioning.

While there are so many unanswered questions surrounding the Pyramids of Giza, it remains clear that these ancient builders had a highly advanced knowledge of physics and engineering.

This sophisticated civilization was responsible for some of the most impressive structures ever constructed; ones that will continue to fill us with wonder for generations to come.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine ; heritagesciencejournal; Britannica.com ; concretenetwork.com ; geotech.hr ; Interestingengineering.com ; secretosdemadrid.es ; sciencing.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.