The Fortune Teller’s Daughter

You need to get married, girl

“You need to get married, girl. I don’t know what’s wrong with you. You’re nineteen years old, gettin’ long in the tooth for many a man,” grumbled Lily’s mother, Zelda, shuffling her Italian tarot cards. “Want me to run the cards and see what they say?”

The air hung hot and sticky in the rundown parlor room. Zelda’s clapboard cottage squatted on the floodplains of Wheeling, just two blocks from the Ohio River. Homes up on the surrounding hills might snag a breeze or two, but no wind made it down to the flats.

Lilly glanced up from her latest Buffalo Bill dime novel, Buffalo Bill at Graveyard Gap. The clerk at the dry goods store was smitten and always passed his Buffalo Bill books along after he read them.

Zelda claimed Lilly’s father had been tragically blown to bits and pieces on a riverboat. Every time she told the story, Zelda would squeeze out a single tear and let it roll down her cheek. Lily knew the drama for what it was — a lie. Her grandma, a white-haired and wrinkled version of Zelda, had spilled the beans.

“Honey, your smooth-talkin’ daddy was a rambler. He just couldn’t stay put. I hear tell he’s out in Oklahoma Territory nowadays, married to a Cherokee lady and they have a dozen little ones. Or maybe it was thirteen little ones. I forget.”

On her part, Lily never could forget the spanking her mother gave her at age seven when she set off on foot for the Oklahoma Territories to meet her dad. She only made it three blocks when Zelda grabbed her up and said, “Never try to fool a clairvoyant. I’ll always know where you are and what you’re up to.” For a year or two, Lily believed her.

Lily went back to her dime novel. A rivulet of warm sweat ran down her back, soaking her cotton chemise and threatening to stain her dress. Her long skirt and sleeves cruelly retained the warmth of the late August day.

“Mama, could we buy a horse? Maybe a nice roan or sorrel?”

“Lord, girl, we ain’t got that kind of money.”

“Well, Mama, what kind of money do we have?”

“Humph,” said Zelda and picked up her gaudiest deck of cards.

Zelda Lamm earned her living telling fortunes, presiding over seances, and otherwise meeting the paranormal needs of the desperate and lovelorn of Wheeling, West Virginia. She could pick out her customers while they were still on the sidewalk, long before they reached her wrought iron gate. Giggling pairs or trios of factory girls, arms linked and long skirts swishing, would be joking as they walked up. They’d shoot their eyes at the wooden sign in her yard emblazoned in curlicued lettering: “FORTUNES TOLD.” Underneath was the silhouette of a crystal ball and beneath that, in smaller letters, “Closed on Sundays and Christmas.” The girls would boldly rap on her door. Other times, Zelda would see a man or woman, older, head down, walking slowly her way and she could tell they needed her care. Zelda knew what it was like to suffer. She’d learned her trade in the tuberculosis sanitarium as a young woman, whiling away the hours and days dealing the tarot cards and waiting for her cure. Zelda knew how to pay attention and give people what they needed or, at least, what they thought they wanted. They didn’t pay much, though.

Zelda flipped over a card — the Queen of Cups. Her black, lively eyes glanced up at Lily.

“Well, looky what we have here, dear.”

“Oh, Mama, stop it! You don’t even believe those cards yourself. I ain’t afraid of not gettin’ a man. I’m more worried about those I do get. I did not enjoy being in the newspapers just because I refused to marry William. No, siree,” said Lily. She picked up her latest pet, a scrawny tabby cat, and gave the feline a noggin rub. “He had no excuse for sending the constable here, but we certainly did a good job keeping the police out, didn’t we? Just you, me, and Grandma and it took the cops three hours to get in the house. No way was I giving him back this furniture. It was a gift.”

“William is a good man. Steady. Got a nice job in the glass factory. I think he’d still have you, even after the lawsuit. After all, he sued ’cause he wanted to marry you. You could just say you changed your mind back to what it was in the beginning when you said you’d be his wife. Women do that every day. But he’s not goin’ to wait forever. Other girls would be happy to have a provider like William.” Zelda shuffled the deck and settled into the walnut rocker. “You’re not makin’ much working at the paint store. Let a man support you.” The last rays of the setting sun lit the white strands in Zelda’s dark hair. In the low light, the remnants of the beauty her daughter had inherited could still be discerned. “Of course, I sure didn’t like him saying to that reporter he’d kissed you four thousand times. What was he thinking of? That just couldn’t be true. Or, at least, he shouldn’t have said it.”

A tiny smile wiggled about Lilly’s mouth.

“Mama, I’m never marrying William. I do appreciate all this furniture he gave me and the mantle clock, but when all is said and done, he ain’t for me. Maybe I will marry someday, but it won’t be William, and would you please stop riffling through those cards? I’ll go fix us a bit of supper.” Leaning over Zelda, Lilly planted a kiss smack in the middle of her mother’s forehead. “I love you, you old rascal.”

Zelda gave the tarot cards a final shuffle, turned one over, and said, “Well, my soul. That looks promising.” She put the deck aside and, pulling out a limp handkerchief, gave a swipe to the small crystal ball on the table.

“It’s Friday night,” Zelda muttered to herself. “Maybe someone in this god-forsaken river town got paid today. We can only hope.”

Soon the aroma of frying catfish wafted into the parlor. Snatches of tuneless singing wafted out, too. Pretty as she was, Lily couldn’t sing worth a damn. With what looked like a sneer, the tabby strode upstairs.

“Probably gonna hide under the bed,” accurately predicted the fortuneteller.

On a particularly crisp Saturday afternoon later that autumn, just about a week away from Halloween, the smell of baking apples laced with cinnamon and possibly a dash of booze filled the cottage. Earlier in the morning, a neighbor lady had dropped in for an emergency tarot reading and paid Zelda with a bushel of MacIntosh apples. Lily, quick for any excuse to bake, had pulled lard and butter out of the ice box, flour from the pantry, and salt from the shelf over the stove. After rhythmically cutting the fats into the flour and salt, she added just the right amount of water to make a soft dough. She then rolled out the dough and cut it into six squares. Her nimble fingers placed one pared and cored apple in the center of each square, tucked a pat of butter in the hollowed core, and sprinkled sugar and cinnamon over it. A final blessing of brandy, then the edges of the dough were brought up to make a package.

Zelda watched her daughter slide the pan of apple dumplings into the black wood-burning stove. The tabby watched, too, hoping for a little something in her bowl.

“You know, for a girl who don’t want to get married, you sure are good with the wifely skills,” opined Zelda. “You should be bakin’ them dumplings for a passel of kids and a husband. Think about it.”

Lily rolled her eyes but gave her mother a pat on the shoulder. “Oh, Mama. You never quit.” Putting the lard and butter back in the ice box, she grabbed a glass bottle of milk and poured a bit of cream from the top into the tabby’s bowl. Lily hung her brown and white checked apron on the hook by the back door. “Let’s go sit down.”

Waiting for the dumplings to bake, Lily and Zelda sat in the parlor mending. Actually, Lily was mending. Zelda was dozing, her head leaning back on the chair’s antimacassar. Her mouth gaped open. Lily kept vigilant watch to assure no flies lit on her mother. Every so often, a snorty little snore would grab Zelda and she’d startle a bit, open her eyes, then go right back to sleep.

Zelda couldn’t sew if her life depended on it, but Lily was right handy with a needle and thread. Lily had crocheted the antimacassar as well as other decorative pieces in the house. She enjoyed embroidering and making elaborate beaded gewgaws, like pincushions and spectacle cases. Her handiwork could match anything coming out of old Queen Victoria’s England. Zelda had a ripped camisole and a spool of thread piled in her lap so if anyone came by, she’d look occupied.

The click of a man’s heels on the sidewalk broke the quiet day. At the sound, Lily looked up from the china button she was sewing on her favorite shirtdress. Like a glorious painting, the front window framed a view of one of the world’s best-looking men walking down the sidewalk. Tall and graceful, his blond hair lay thick and soft above a straight nose and chiseled chin. Lily hopefully held her breath and was rewarded by a knock on the door. She rose to answer it as her mother sputtered awake.

“Yes, may I help you?” Lily asked in her softest voice, the one which usually reeled in the local boys and men. Her black eyes met his grey ones. “Are you here to see the fortune lady, my mother?”

“What? No, not really. I’m here to see about the room to let,” he said. “I read your advertisement in the paper and I’m new to town.”

“Oh, you must be mistaken. The room is in the house next door, but I happen to know the family just left on an errand. Would you like to come in and wait here for them? Maybe have a cup of tea or coffee?”

Drawn by Lily’s daintiness or maybe the cinnamon aroma of the dumplings, the man stepped in. “Well, if you don’t mind, I’d love to rest a minute and maybe learn a bit about Wheeling. I’m from Steubenville and don’t know a thing about this area, except it’s the skinniest sliver of West Virginia.”

The rest of the afternoon went by quickly. Mr. James Yardley (as the handsome fellow introduced himself) chatted knowledgeably about goings on, all up and down the mighty Ohio River. He knew everything there was to know concerning the barges and boats carrying goods from Pittsburgh to Cincinnati and had even been to New Orleans. Yardley praised the bock beer in Cincinnati and the square doughnuts in New Orleans.

“But I have to say, I have never tasted an apple dumpling to compare with yours, Miss Lamm,” said Yardley.

Accustomed to praise, Lily gave the tiniest nod.

Zelda hopped in. “Oh, my daughter is one of Wheeling’s best bakers. It’ll be a lucky man who weds her, that’s for sure.”

“I’m sure you’re right, Mrs. Lamm,” said Yardley as he pulled the biggest gold watch the Lamm women had ever seen from his his vest pocket. “Well, looks like the neighbors aren’t coming back anytime soon. I’ll have to say good bye for now but wonder if Miss Lamm would like to go horseback riding tomorrow, if I may be so bold. We’d ride at the Warren farm and woods, just on the edge of town, Mrs. Lamm. Totally safe.”

Zelda could not control the grin splitting her face. “Well, dear, what do you say?”

“I’d love to,” said Lily.

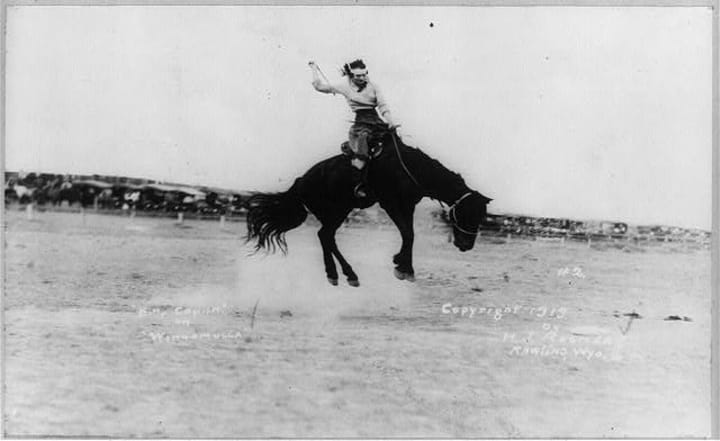

James mounted a huge dapple grey on Sunday, nearly seventeen hands tall. Mr. Warren brought out a flashy sorrel sporting a side saddle for Lily. Lily knew full well how to ride astride, but gamely mounted the sorrel. Perched atop, she hooked her right leg around the fixed pommel and snugged her thigh against the lower pommel, the leaping horn. She made sure her spine lined up with the horse’s, gave a cluck, and rode off. Startled, James urged his grey after her. Even riding sidesaddle could not ruin Lily’s joy or slow her down. The breeze brushed against her cheeks and swept any stray strands of hair off her face as she and James trotted through a meadow of tall grasses.

After trailing through a cool woodlot, they came out at the top of a hill. Rows of field corn, dry and brown and destined to feed Mr. Warren’s Holstein cows, lined the hill. Laughing, Lily galloped down the rows, occasionally sticking out her left foot and lopping off a cornstalk or two. James tried to keep up.

Back at the barn, James encircled Lily’s waist with his hands. Effortlessly, he lifted her off the saddle and placed her on the ground.

“Oh, James, thank you so much. I’ve not had such fun in months!”

James grinned.

Over the winter, James courted Lily. He always spent a goodly amount of time chatting up Zelda. More often than not, he’d bring flowers for Zelda and a bit of expensive lace or a yard of silk for Lily. Once he brought a box of chocolates in a burgundy satin-covered box with a white bow. Grandma had somehow known enough to drop by for a visit. All four spent a delightful afternoon sipping coffee and eating the chocolate confections. They competed to see who could most accurately guess the filling of each chocolate before popping it into their mouth. Not surprisingly, Zelda won.

James’s visits always happened on a Saturday between the hours of one and three. Lily invited him to dinner during the week and during the weekends, but James said he had to work weekdays. He sold insurance for barges which sounded terribly boring to Lizzie, so she never asked about his job. Instead, she peppered him with questions about his travels — what the cities, towns, and farmland looked like, how far west he’d been, how far south, had he ever met a Cherokee, and such like. James regaled Lily with his exploits. He’d jumped on a train just as it left a station, been on a stage coach when it was robbed by bandits, and done all manner of exciting things. His father fought in the Civil War only to die with Custer at the Little Big Horn. Lily was thrilled. Zelda just sat at her round table and listened, turning over tarot cards one by one. Every so often, she’d raise her head with a puzzled expression on her face.

Saturday and Sunday nights James worked on his patent for a hoist to make loading barges easier. He couldn’t come over for dinner those nights, either. Lily was impressed, but the tabby remained aloof.

“I do so love hearing about all the places you’ve been and things you’ve done, James,” said Lillie one Saturday afternoon. “I have always wanted to travel myself and see the world, but I guess adventures are just more of a man’s thing, don’t you think so?”

“Well, of course. You don’t want to be rambling around out in public. Women belong at home. Look at all the fun you have sewing and cooking. Why, you might have even more fun if you ever settled down and had a few babies. Think about it.”

“I don’t know, James. Who’d put up with me? I know I have a temper and am a willful woman. And what about mother — she’d be so lonesome.”

James paused, his eyes rolling up toward the left as he thought. “Yes, Zelda is a special lady, isn’t she?” The tabby sat on the mantle and glowered at James, but Lily didn’t notice. She snuggled against her suitor and breathed in the scent of cedar from his wool jacket.

The following Saturday, James stopped by at one in the afternoon and asked Zelda if she’d go on a short walk with him. Miffed to be excluded, Lily went to the kitchen. James and Zelda shared a glance when the rattling of pots and pans crescendoed to a crash as Lillie dropped an enameled roasting pan on the floor. “Drat!”

James and Zelda slid out the front door. Twenty minutes later, James returned alone to the smell of roasting beef. Lily was singing a cowboy lullaby, off-key as usual.

“Your mother’s visiting the neighbors’ house, Lily dear,” said James. “Come out from the kitchen. I’ve a question to ask you.”

Lily crept out, her frown making a crease bloom between her eyebrows. Flour smudged one cheek and the front of her apron.

“What?” she said grumpily.

James got down on one knee, pulled out a small white and cream box from his pocket, and asked her the question she had expected.

The wedding was a low-key affair, very low key. James handled the legal aspects, arranging for the paperwork and Justice of the Peace. Grandma, Zelda, and Lily’s friend Pansy formed a friendly half-circle of support behind the couple as they exchanged their vows in the cottage parlor. James wore his grey wool suit. Lily was resplendent in her mother’s ivory silk wedding gown. Her bouquet of deep pink Madam Isaac Pereire roses, cut by Zelda from the neighbor’s yard, added a heady scent. Lily had baked a Lady Baltimore cake to celebrate, with plenty of chopped dried fruit between each white layer. James said he’d never tasted a cake so fine. The couple would live with Zelda until James’s patent was done.

James left soon after the wedding on a business trip to Louisville. Two days after bidding him farewell, Lily sent a message to her boss at the paint shop:

Dear Mr. Allen,

I’m sorry but I won’t be able to work today as I have a very bad cold. I don’t want you or the customers to catch it. I hope to be better in two days and will be in to work then.

Thank you,

Your faithful employee,

Lily Lamm Yardley

The letter was a bit of a fib. Lily planned on playing hooky with Pansy. She’d run into her friend at the dry goods store while picking up the next Buffalo Bill dime novel. (Buffalo Bill’s Death Grapple promised to be a truly thrilling read and Lily was particularly taken with its luridly colored cover.)

Pansy lived with her parents who had a bit of money, so she didn’t need to work. Her steady beau Harold had finally proposed. Pansy was preparing for a July wedding with all the trimmings. In fact, Lily had Pansy’s bridal veil back at the cottage. She had already added most of the imported lace rosettes to its edge. As she sewed the lace, she’d daydream about how beautiful it would look against Pansy’s auburn hair. A stocky girl, Pansy’s dimples added just the dash her oval face needed to be quite attractive. But more importantly for Lily, Pansy was loyal and honest.

The dry goods clerk pretended not to eavesdrop as Pansy and Lily plotted.

“Don’t you think we deserve a day to ourselves, Lily? I’ll be married soon, and you already are. For all we know, this time next year we’ll each be up all night with a new baby.”

Lily agreed, especially if things kept on the way they were going so far with James. The man was quite amorous. Lovemaking with her husband brought her pleasure, but she dreaded the potential end result. The dry goods clerk felt his cheeks redden, and he moved farther down the counter, away from the women.

Pansy and Lily, ignoring the clerk, hatched a scheme to rent a buggy and drive over to Ohio for the day. They’d cross the historic Wheeling Suspension Bridge then go north into Bridgeport to shop and have lunch. Pansy knew a small hotel serving ladies’ lunches of fancy sandwiches and lemonade.

Things began auspiciously. Lily, as usual, took the reins. She’d brought a pair of driving gloves and packed two apples for the horse in her bag. At the livery, the stableman had harnessed a sturdy beige Belgian with a straw-colored mane and tail to the buggy. The gelding rolled a brown eye at her as if to say, “Are you sure you can handle me?” Lily was very sure.

The buggy rattled over the cobblestones as they neared the muddy brown Ohio River, then rolled more quietly across the bridge.

“I adore this old bridge, Pansy, don’t you? I always think the cables are just like angel’s harp strings. I don’t get to cross over to Ohio often, but I do see the bridge on my walk to Mr. Allen’s paint shop.”

“Did he complain about you wanting the day off, Lily?”

“Oh, no. No problem there.”

Pansy and Lily chattered away as they drove into Bridgeport and continued the conversation at the hotel. The waiter had seated them, upon their request, at a table by the front window. From this vantage point, they could see the West Virginia hills across the river and a few of Bridgeport’s shops. Muffled shouts and rumbling from carts on cobblestones carried up from the river’s edge.

Their waitress arrived, neat as a funeral director in a black dress and white apron. Lily asked for an egg salad sandwich. Pansy ordered a liverwurst on rye with onion and tomato.

“I can’t believe you eat braunschweiger, Pansy.” Lily’s grandma was Pennsylvania Dutch, so her family tended to use German terms.

“Well, liver’s full of iron and good for me. I like it.”

“I guess that’s what’s important, “chuckled Lily.

Suddenly serious, Pansy looked up from her lemonade, “How is married life, Lily? What’s it really like? Are you happy?”

“Oh, yes, I am…” Lily stopped abruptly, her next words falling away. Her heart somersaulted at the tableau now presenting itself through the hotel window. Walking arm in arm down the Bridgeport sidewalk strode — no, positively sashayed — James and a redhead. Her hourglass figure fetchingly filled out a plum-colored dress. At his side, a tow-headed boy skipped and hopped, the mirror image of James.

And so ended Lily’s marriage. Or what she thought was her marriage. Actually, the Justice of the Peace had been James Yardley’s drinking buddy Joel. James had dodged bigamy by faking his wedding to Lily.

Lily pondered her options. As Zelda noted, “If you haven’t thought of murder, you haven’t thought of everything,” but Lily was no murderer or even a slapper or a kicker. She dropped James cold.

A few weeks later, Lily sat in the walnut rocking chair, beading a change purse for Pansy’s trousseau. Using a skinny needle in her right hand, she skewered three yellow beads from her left palm. A floral decoration of pansies (what else?) and ivy was emerging as she sewed on the beads. The tabby rubbed against her ankles and purred contently. She glanced up from her work.

“Mama, I believe I’ve learned from William and James. I think I’ll be fine.”

Zelda turned over the Ace of Pentacles and smiled to herself. “Yes, I think you’re right.”

A week before her wedding, Pansy dropped by for coffee and to pick up her veil.

“Now, Lily, I went ahead and bought tickets for us. Once I’m married, I won’t be able to call my time my own, so I thought we should take a day off and spend it together. I’m not telling you where we’re going — just be ready tomorrow morning and I’ll pick you up at nine. Tell your mother you won’t be home till supper. What do you say?”

Never one to turn down time with Pansy, Lily acquiesced.

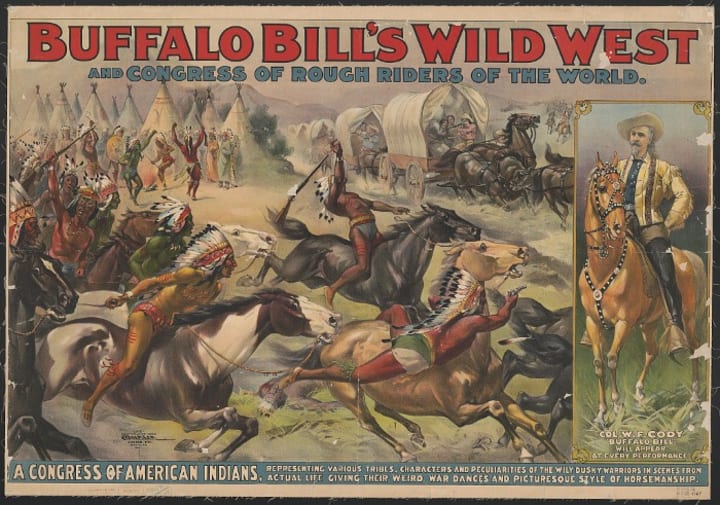

The train trip to Washington, Pennsylvania went quickly. Time always flew whenever Pansy and Lily got together. Lily thought the train more crowded than usual. Reaching Washington, the pair stepped onto the platform. Colorful banners announcing “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show” festooned the station house. Young boys hawked souvenirs.

“Oh, my gosh, Pansy! Are we going to see Buffalo Bill?”

“Absolutely. I thought you’d like it.”

Lily hugged her friend.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show sparkled with drama, violence, suspense, romance, risk, and hyperbole. Lily’s hands tingled from clapping. Her voice hoarsened from cheering. After the matinee, the two young women nibbled on popcorn and wandered through the American Indian village. Toddling Lakota children played with their siblings under their mothers’ watchful eyes. Campfires scented the air with wood smoke. Behind the village, horses grazed in a roped-off paddock. Farther off, along a creek, wooly American bison wandered knee deep in the water. A dog pounced and barked at a bison calf, fruitlessly attempting to engage the beast.

Leaving Pansy as she admired a piece of Cheyenne beadwork for sale, Lily wandered off to speak with a few of the performers. One cowboy pointed out a manager and Lily walked over to him to chat.

“You seem pretty quiet. Are you OK? Tired?” asked Pansy on the train ride home. She flicked a piece of straw off her hem. Fields of corn and rolling hills sped by. Two boys pummeled each other in the seat two rows up.

“I’m fine. I can’t thank you enough for this, Pansy. Listen, I think I know what I want to do with my life,” said Lily. She told Pansy.

The next morning Lily hugged her mother and shouldered a worn canvas traveling bag. Zelda wasn’t worried. She’d just flipped over the Sun card that morning.

Lily joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show as a lady equestrienne. Within two years, she was riding buffalo and bucking broncos. Within five years, she was Lily Lamm, Lady Bucking Broncho Champion of the World. Lily traveled to England, South America and all over the United States. She performed for royalty, shook hands with Teddy Roosevelt, and married a rodeo clown. Lily Lamm had her own adventures. Lily had no regrets.

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.