Strange Fruit

a short story

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

A lot of people have sung these words, but my grandmother always said they belonged to Lady Day. She may not have written them, but she certainly owned them. Nan loved Billie Holiday as if she were family, and cried as such when she passed on five summers back.

I’ve always thought Nan could have made a go of it as a singer, professionally I mean, if she didn’t have my mother and uncles to raise. But to Nan, family comes above all else (except for the Lord, of course), making me one of the fortunate beneficiaries of her angelic voice. The other was the church. She’d sing me to sleep with lullabies as a child and still leads the church choir in song every Sunday.

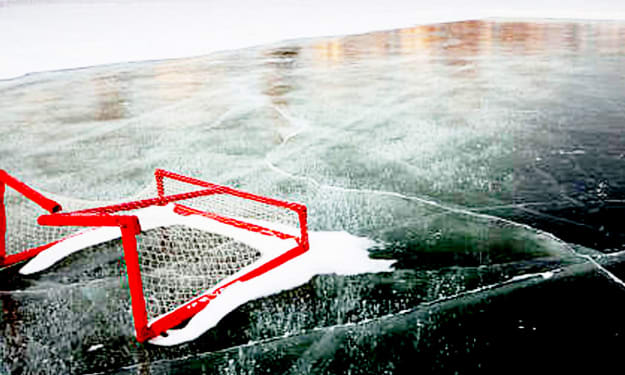

And it’s her voice I hear—Nan’s not Billie’s—singing those words to me now, in her sweet bedtime lullaby voice, as I walk through the meadow toward the small crowd. They’re waiting for me, gathered around in the shade of an old pear tree, seeking refuge from late June’s midday sun. I know the tree well. My school bus passed by it every day on the drive across town. I’d stare out the window, thinking: what a survivor.

I see a few familiar faces and notice most are dressed in their Sunday best, it being Sunday and all. But even as we get closer, none make eye contact with me, and I wonder why they’re here. Have they come to hear an apology, to witness a man repent? Or have they come for something else? I think about what to say. How to act. Though I know it doesn’t matter to minds made up long ago, as soon as they left the womb.

Of all the things passed down through the family tree, singing isn’t one of them. A fact I’ve proven time and again with my marked inability to carry a tune. But I’ve never been afraid of using my voice. Of speaking up. Nan said I had the gift of gab until she overheard someone call me an orator. And that’s all she’s called me from that day on. An orator. As though the mere mention of the noun imbues me with some special power or prestige. Even though, for a man like me, power and prestige are a double-edged sword.

“When I was your age,” Nan said, “ain’t no way anybody be calling a boy like you an orator. Mouthy, sure. Smart, maybe, but always too smart, followed by for his own good.”

And I am smart. It’s what got me where I am today. My knowledge, my beliefs and convictions, and my gift of gab. While I may not be able to harmonize or stay in key, people listen to what I have to say. They come from all around, even out of state, to hear me speak.

But not everybody likes what I have to say.

It’s an unexpected, impromptu gathering. The tree stands alone in the middle of a tranquil green pasture, at the top of a hill so gentle it only exists to the eye from a certain perspective. From the direction we approach, I can just make out the curvature of the grass, small assemblage notwithstanding. The tree is not part of an orchard and being a cross-pollinator it, therefore, hasn’t born fruit in decades, probably even longer. Local legend says it was planted by French colonists back around 1760 or so, making it just over two hundred years old. However, their attempts at agriculture in the region were as successful as their efforts at hanging onto the great state of Mississippi. But somehow this tree survived the two bloodiest wars on American soil. Wasn’t it Winston Churchill who said that solitary trees, if they grow at all, grow strong?

But such pith is a privilege.

For a brief moment, I wonder, not for the first time, what things would be like if the French had been able to stick around. Or the Spanish right after them. Or even the British. Or if none of them had ever come at all. I reckon the Natchez would have been alright with that. Same goes for my roots. The notion distracts me for a moment and I almost smirk. Somehow. Even I don’t understand why. I guess that’s how the mind works during moments like this. Taking in everything it can, as fast as it can. It’s like packing a suitcase when the house is on fire, but I can’t see the flames. I can’t feel the heat even though I know it’s there. So a kind of involuntary stoicism kicks in that some might regard as bravery. Or cold-bloodedness.

Deep breaths. One foot in front of the other. Chin up. Dignity.

My entourage and I approach our patiently waiting congregation. A few mutters and mumbles flow through the flock like an insipid summer breeze, but mostly, they remain silent. This is about me, not them. (Even though I might dispute that perspective.) Through the quietude I can almost hear the air transform in response to our proximity to the group, becoming thicker and heavier with body heat and breath. Nature’s open field freshness is supplanted by recently digested lunches and waning perfumes mixed with sweat.

Mr. Clarkson, who owns the greengrocer a few blocks from Nan’s church (which used to be mine as well), removes a white handkerchief from his shirt pocket and dabs his face and forehead, then wipes the back of his neck. Mrs. Barnes is also in attendance, which surprises me at first, due to her clandestine relationship with my good friend Elbert. But registering the look on her husband’s face, and the grip he has on her arm, I figure maybe that’s the point.

I’ve gone over the speech a thousand times in my head. Probably more. Definitely more. And now, as I’m a half-dozen steps from the podium, I feel myself drawing a blank. Beads of perspiration form on my forehead—as if I’m no different than my audience—and my pulse quickens. Panic rises inside me like a brass teakettle coming to a boil. It’s only a matter of time before the lid starts shaking, alerting everyone within in earshot that it’s done. That I’m done.

I wish I had my notes.

It’s a pointless action, but I pat the outside of my pants pocket to double check. Even though my hands are tied and I’ve got no speech to make. Nobody has come here to listen to me. It’s not that kind of gathering.

We reach the broad acme of the soft round hill. I step onto the wooden crate that somebody arranged before my arrival and look out over the crowd. Stiffening my jaw, I clear my throat and all the words I want to say to these people come flooding back like a tsunami. But if you see the tsunami coming, it’s already too late. The same is with the words I’ve been fine-tuning since sophomore year of high school, in the event this should ever happen to me. Not that these people would even let me speak. But in my dreams they did.

In my dreams they listened.

In my dreams I changed minds.

But this isn’t a dream. This is a nightmare. And as they drape that rope over my head and around my neck, the words of my well-rehearsed diatribe fade away to the recesses of my mind. Into nothingness. And I find serenity, becoming one with the tree that stood steadfast through two great wars. Leaving my body, I ponder the difference between a poplar and a pear tree. And all I hear is Nan’s voice, singing me a lullaby one last time.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

About the Creator

Russell Cordner

Japan-based multi-genre writer for adults and YA, mainly crime and speculative fiction.

My debut novel, Inherit Guilt, was published in June 2021.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.