Menabilly, My Love… Part Four: ‘Queer’

A series of articles dedicated to the mysteries of 'Rebecca' by Daphne du Maurier, and their real-life inspirations. Based on the Rashleigh family history and 'Rebecca Notebook'.

‘Deaths. On the 17th inst., at Ventnor, Mary Frances, widow of Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., of Menabilly, Cornwall, aged 25.’ (‘The Hour’, 23 February 1874)

The death of Mary Frances Labouchere (1848-1874), the youngest daughter of an English banker, John Peter Labouchere (1798 -1863), was an inspiration for creating the circumstances of the death of her fictional counterpart, the late Mrs de Winter, in the ‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier. But she was not the main inspiration in this regard. It was her husband, Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., (1845-1872), the eldest son of Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905), of Menabilly. In particular, his death that had occurred a year earlier, in December 1872:

‘The remains of this lamented young gentleman were brought from London to Par on Thursday evening, and rested for the night in the chapel at Menabilly. On Friday morning they were conveyed to Tywardreath church… […] The service in the Church and at the burial place was read in the most impressive manner by the Rev. George Ross, and the Rev. Anthony Thorold respectively. The body was carried into the Church by the principal tenants of the estate, and afterward, deposited by them in the family vault in the churchyard. The utmost sympathy was evinced by all classes of persons composing the large gathering of friends and neighbours…’ (‘The Morning Post’, 18 December 1872)

It is important to note that obituaries and other announcements that appeared in the newspapers of the time were paid advertisements and a source of funds for publishers. The accuracy and the content were not really guarded. Also, due to slow communications, local counties produced their own publications, usually weeklies, that were circulated amongst the inhabitants of the area. London papers were more expensive, targeted specific segments of the society, and also were slow to reach other parts of the country. ‘The Morning Post’, a conservative daily publication, in which the obituary for Jonathan Rashleigh, jun. appeared was said to be the preferred reading of the aristocracy. Therefore, the obituary was specifically published for the eyes of upper classes.

Regardless where the obituary appeared and unlike the obituary portrait, which, apart from the above piece, contained other ‘glorious’ elements of his life, Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., (1845-1872) was a rather ordinary man with no particular interests or aspirations that were worth recording, mentioning, or publicising. Perhaps, Daphne du Maurier while studying the Rashleigh’s family history noticed the same paradox, and, in the ‘Rebecca’, expressed her thoughts in this regard in the description of a hotel room of Mr de Winter, in particular Maxim de Winter: ‘I glanced round the room, it was the room of any man, untidy and impersonal.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

This seemingly ordinary young man was the eldest son of Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905), the younger brother of William Rashleigh MP (1817-1871) of Menabilly, the largest estate in Cornwall at the time. Since his chances of inheriting estate and thus becoming a landowner were slim, as he was the third in line, after his uncle and father, provided William Rashleigh MP had no sons, he was expected to find a preoccupation and dedicate himself to it. Yet, records of educational and military institutions and the absence of any service related mentions in the press witness otherwise. For this and also other reasons, his obituary was full of twisted facts and misrepresented information to deliberately supply a false impression of this person. An obituary picture was much better than the person it had been painted from.

The first misinterpreted fact was the place of Jonathan Rashleigh’s birth. This was done to add an air of importance that he did not really have. Contrary to the line in the ‘Royal Cornwall Gazette’: ‘The deceased gentleman was born at Menabilly, May 26, 1845’, this young man was born in London at 3 Cumberland Terrace, Regent’s Park, where his father, Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905) ‘not expecting to inherit the Rashleigh family estate, settled with his wife’, Mary Pole Stuart (1823-1852), ‘seemingly as a gentleman of leisure.’ (BNS Research Blog, by Hugh Pagan, 1 October 2019) When Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., was seven years old his mother died leaving his father a youthful widow who had to raise his five children on his own. At the time, having no particular occupation, his father was receiving an annuity (Census 1851), and called himself a ‘fund holder’ (Census 1861). What funds exactly he was holding is not clear though.

The primary education, Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., as his father had done before him, received at Harrow, a public boarding all-boys school. This fact is reflected in the ‘Rebecca’ as a series of coded references. One of such references is connected to the school’s uniform and is inserted in to the ‘confessional’ speech of Maximilian de Winter as a description of Rebecca’s sandals, which she wore during the fatal conversation: ‘I remember watching that foot of hers in its striped sandal swinging backwards and forward, and my eyes and brain began to burn in a strange quick way. […] ’Still that foot of hers, swinging to and fro, that damned foot in its blue and white striped sandal.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

The blue and white stripes of the sandal is a vital clue to whom Maximilian de Winter has his fatal conversation with, for it refers to the blue and white colours of the Harrow school which was and is the all-boys school. Another hint is ‘swinging backwards and forward’ foot. It concerns the school’s unique style of football, the Harrow football. The ‘backwards’ and ‘forward’ are reference to the names of the positions in the game: the backs and forwards. Thus, the opponent of Maximilian de Winter dressed in a ‘blue and white striped sandal’ is not a ‘she’ but a ‘he’, the real-life counterpart of whom is Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., (1845-1872).

The swapping of ‘she’ for ‘he’ also happens in the narrator’s storytelling. Especially it concerns the recollections and references connected to the boarding school and its schoolboys:

‘I remember that, for I was young enough to win happiness in the wearing of his clothes, playing the schoolboy again who carries his hero’s sweater and ties it about his throat choking with pride, and this borrowing of his coat, wearing it around my shoulders for even a few minutes at a time, was a triumph in itself, and made a glow about my morning.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

In this context, ‘his hero’ refers to the school’s prefects – usually students in fifth to seventh year. The ‘sweater’ and ‘his coat’ are the elements of the Harrow school uniform, the everyday dress, that among other items included a dark blue sweater or jumper and a dark blue woollen coat. Thus, being able to wear ‘his hero’s sweater’ and ‘borrowing of his coat’ relates to senior and junior Harrow school boys and their relationships that might have involved some admiration and romantic feelings.

Every time the narrator turns into a ‘he’, the dynamics of the narrator-Mr de Winter relationship changes from a woman-man to a man-man. One of such inversions occurs when the narrator compares Mr de Winter to ‘a sixth-form perfect’ i.e. ‘prefect’:

‘I was like a little scrubby schoolboy with a passion for a sixth-form perfect, and he kinder, and far more inaccessible.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

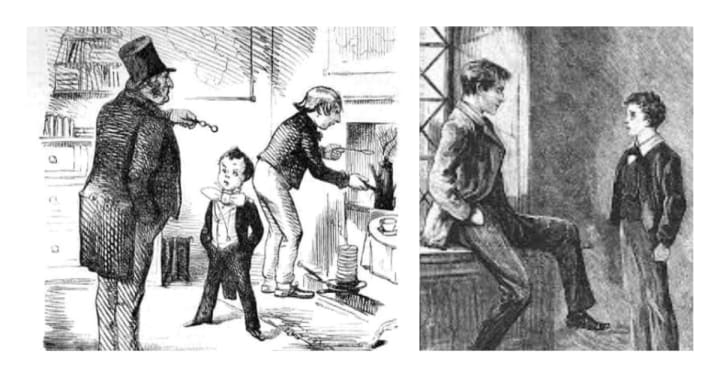

In boarding schools, the prefects had considerable power, including administering corporal punishment. The theme which resurfaces in certain passages throughout the book, but mainly relates to the parts of ‘he’ narrating:

‘At first I had been shocked, wretchedly embarrassed; I would feel like a whipping boy who must bear his master’s pains when I watched people laugh behind her back, leave a room hurriedly upon her entrance, or even vanish behind a Service door on the corridor upstairs.’ […] ‘Later her friends would come in for a drink, which I must mix for them, hating my task, shy and ill-at-ease in my corner hemmed in by their parrot chatter, and I would be a whipping-boy again, blushing for her when, excited by her little crowd, she must sit up in bed and talk too loudly, laugh too long, reach to the portable gramophone and start a record, shrugging her large shoulders to the tune.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

In the above passages, the inversion of ‘she’ into ‘he’ occurs twice. In the case of the narrator, and in the case of Mrs Van Hopper, who, in this context, turns into a fag-master and the narrator into her fag. The type of relationship and the emotions and feelings of the narrator attached to it reference fagging - a traditional practice in the British public schools whereby young pupils were required to act as personal servants to the eldest boys. ‘Those who hope to rule must first learn to obey…’ (Harrow master, C.H.P. Mayo) The phrase ‘hating my task, shy and ill-at-ease’ describes the resentment of taking orders and obeying, showing a person who would not be able to properly ‘rule’ later, for she/he does not easily accept structure and hierarchy.

The scene picturing the half-wit, Ben, whom Jack Favell believes to be a crucial witness in his accusations against Maximilian de Winter tackles the theme of corporal punishment and the reward system for fags practiced in the boarding schools:

‘He's been frightened at some time,’ said Colonel Julyan. ‘He was showing the whites of his eyes, just like a dog does when you’re going to whip him. ‘Well, why didn’t you?’ said Favell. ‘He’d have remembered me all right if you’d whipped him. Oh, no, he’s going to be given a good supper for his work tonight. Ben’s not going to be whipped.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

In this particular scene and context, Colonel Julyan becomes a ‘school prefect’ and Favell speaking about whipping and the reward for ‘his work’ refers to the powers the school prefect holds. Also, the scene shows the distribution of power between the two opponents, and that Ben is certainly not Favell’s ‘fag’ and therefore he has no influence in deciding what the half-wit gets and what he does not. ‘A good supper for his work’, in this context, is a part of the rewards system that existed between fag-masters and their fags. At the end of semester fag-master were expected to give a monetary ‘fag tip’ to their subordinates or reward them somehow else. In the case of Ben, it is ‘a good supper’.

A fag perspective on the fag-rewards are expressed by the narrator in the ‘he’ role when ‘she’ laments on the subject in her subordinate-boss relationship with Mrs Van Hopper: ‘I was glad she was going, glad I should not see her again. I grudged the months I had spent with her, employed by her, taking her money, trotting in her wake like a shadow, drab and dumb. Of course I was inexperienced, of course I was idiotic, shy, and young. I knew all that.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

In another scene, the fag-rewards are looked at from an entirely different perspective. The one that is regarded as ‘bribing’ of the fag by a third party to alter the truth in one’s favour:

‘Someone has got at this idiot and bribed him. I tell you he’s seen me scores of times. Here. Will this make you remember?’ He fumbled in his hip pocket and brought out a note-case. He flourished a pound note in front of Ben. ‘Now do you remember me?’ he said.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

It is believed that fagging system had its share in spreading of homosexuality and sexual abuse in the British all-boys boarding schools. Professor, Christopher Tyerman, observed that in some situations fagging could either encourage or conceal sexual activity between boys, and that fagging began to decline at around the same time as homosexuality was eradicated as an acceptable part of the school environment.

In the ‘Rebecca’, Daphne du Maurier did not expose homosexuality, instead she concealed it by weaving certain ambiguities into contexts of selected scenes and conversation. One of the most important scenes in this regard is the ‘confessional’ speech of Mr de Winter, in particular, the row between him and his first wife. Even though, in the text, Mr de Winter refers to his opponent as she, it is not a woman he speaks to but a man. In order to conceal this fact Daphne du Maurier applied an inversion but at the same time left certain descriptions obvious, in order to draw the readers’ attention to these points.

For example, she had made her ‘Mrs de Winter’ move and express herself in a very masculine way:

‘She threw back her head and laughed.’ […] ‘She stood watching me, rocking on her heels, her hands in her pockets and a smile on her face.’ […] ‘Suddenly she slipped off the table and stood in front of me, smiling still, her hands in her pockets.’ […] ‘She waited a minute, rocking on her heels, and then she lit a cigarette and went and stood by the window. She began to laugh. She went on laughing. I thought she would never stop.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

‘Rocking on her heels, her hands in pockets’ is a posture that describes a man. Usually, women do not rock on their heels during conversations, for they have got heels on their shoes and it would be rather difficult to perform such gesture, even with a small heel. It would simply break. This suggests that Mr de Winter had a row with a man and the reason for the row and resenting each other was rooted in the non-Christian conduct of Mr de Winter’s opponent. The very opposite of what the twisted obituary of Jonathan Rashleigh (1845-1872) referred to: ‘high principle of character and Christian tone of conduct which he always manifested.’ ('Royal Cornwall Gazette' 21 December 1872)

Interestingly enough, before appearing in the obituary, this ‘Christian tone of conduct’ had not been recorded or written about anywhere else in the press. Perhaps, Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., was very good at concealing it from the world, but then what was the use of it, really. It is more likely, however, that it is this very conduct that he was missing and therefore could not meet certain expectations of his family. His non-Christian conduct could be related to his homosexual inclinations and loose behaviour that in the long run had become the source of constant worry for his father, Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905). Especially after he inherited Menabilly and became one of the biggest landowners in Cornwall. Therefore, his eldest son’s out of line inclinations could seriously damage his reputation.

In the Victorian times homosexuality was only considered a crime if it was proved that an individual had a sexual intercourse with another man. This could be done only by producing a witness. Without a witness, there was no case, therefore an individual could not be accused.

An illustration of this is a scene in the ‘Rebecca’, where, whilst talking to the narrator, Jack Favell includes a servant, Robert, into the conversation by hinting at his certain amorous adventures to which he was a witness. The scene is inverted as with other concealing scenes, so girls becomes boys, and ‘she’ turns into ‘he’:

‘Well, Robert?’ said Favell, ‘I haven’t seen you for a very long time. Still breaking the hearts of the girls in Kerrith?’ Robert flushed. He glanced at me, horribly embarrassed. ‘All right, old chap, I won’t give you away. Run along and get me a double whisky, and jump on it.’ Robert disappeared. Favell laughed, drooping ash all over the floor. ‘I took Robert out once on his half-day,’ he said. ‘Rebecca bet me a fiver I wouldn’t ask him. I won my fiver all right. Spent one of the funniest evenings of my life. Did I laugh? Oh, boy! Robert on the razzle takes a lot of beating, I tell you. I must say he’s got a good eye for a girl. He picked the prettiest of the bunch we saw that night.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

Robert being ‘horribly embarrassed’ and Favell promising not giving him away shows that it was not just about going out and getting drunk and fooling around with some girls. This would be normal for any young man of the status of Robert. The embarrassment came from the fact that Favell had witnessed more than he should have done. The same situation applies in regards to the half-wit, Ben, who is also a witness but to a different ‘crime’, of which Favell had never been a part, but wanted Ben to testify he was. Ben’s admitting of seeing Jack Favell going with Mrs de Winter to the cottage in the woods would provide evidence that Jack Favell is not a homosexual.

‘You know who I am, don’t you?’ repeated Favell. Still Ben did not answer. Colonel Julyan walked across to him. ‘You shall go home in a few moments, Ben,’ he said. ‘No one is going to hurt you. We just want you to answer one or two questions. You know Mr Favell, don’t you?’ This time Ben shook his head. ‘I never seen ’un,’ he said. ‘Don’t be a bloody fool,’ said Favell roughly; ‘you know you’ve seen me. You’ve seen me go to the cottage on the beach, Mrs de Winter’s cottage. You’ve seen me there, haven’t you?’ ‘No,’ said Ben. ‘I never seen no one.’ ‘You damned half-witted liar,’ said Favell, ‘are you going to stand there and say you never saw me, last year, walk through those woods with Mrs de Winter, and go into the cottage? Didn’t we catch you once, peering at us from the window?’ ‘Eh?’ said Ben. ‘A convincing witness,’ said Colonel Julyan sarcastically.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

In the ‘Rebecca’, the homosexual affair is weaved in to the context of another love affair. The details of these love affairs that are connected to the real-life events are interlaced in the scenes of Mr de Winter’s ‘confession’ and Jack Favell’s blackmailing and ‘investigation’ that follows it. Both stories concern romantic relationships, yet each of different nature. One involves Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., (1845-1872) and his lover, represented in the book by ‘Rebecca’ and Jack Favell, and the other, concerns a love affair of Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905) and the wife of his son, Mary Frances Labouchere (1848-1874) represented in the book by Rebecca in the status of the late Mrs de Winter and Maximilian de Winter.

In order to distinguish between different Mrs de Winters, Daphne du Maurier attached the following indicators - ‘the first’ and ‘the late’. These indicators can mean the first and the second, as in relating to two separate women in order of importance or sequential order, also the first, as in the wife of a senior member of the family, and the late as in the one who has died. Transferred to the real-life situation in the Rashleigh family it reveals the following dynamics: the first Mrs de Winter is the second wife of Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905), the late Mrs de Winter is the wife of his son, Mary France Labouchere (1848-1874), she-Rebecca is the late Mrs de Winter, and he-Rebecca is Maxim de Winter whose real-life counterpart is Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., (1845-1872). In other words, there are two couples: Maximilian de Winter and his wife, and Maxim de Winter and his wife. Both wives are called Mrs de Winter, as both of their real-life counterparts were called Mrs Rashleigh. Both real-life women are young in comparison to the main figure of the family intrigue – Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905). In 1869, when the first Mrs Rashleigh married him she was 33 y.o. In 1872, when his eldest son, Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., died, she was 36 y.o. At the same time, in 1870, the late Mrs Rashleigh was 21 y.o. when she married Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., and, 23 y.o. when, almost two years later, she gave birth to her child, an only son, John Cosmo.

It is the second wife of Jonathan Rashleigh (1820-1905) that the fictional Maximilian de Winter refers to when he says to the narrator who, in this case, turns into Mary Frances Labouchere (1848-1874): ‘‘I ask you’, he said gravely, ‘because you are not dressed in black satin, with a string of pearls, nor are you thirty-six.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier) On its own the statement does not make any sense for it seems to refer to some collective image of a woman of 36, but when put into the context of real-life characters of Rashleigh family it makes perfect sense. The narrator is indeed not 36 nor she is the official wife of Maximilian de Winter.

In the book, the queerness of Mr de Winter is pointed out by Mrs Van Hopper, who in certain scenes turns into mother of Mary Frances Labouchere – a very rich widow, Mary Louise (Dupre) Labouchere (1808-1875), and Mary Frances, her youngest daughter, becomes the narrator.

‘Attractive creature,’ she said, ‘but queer tempered I should think, difficult to know.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

What was outlined by Mrs Van Hopper in the beginning of the book becomes apparent to the narrator towards its end:

‘Perhaps it’s a good thing; it’s made me realize something I ought to have known before, that I ought to have suspected when I married Maxim.’ ‘What do you mean?’ said Frank. His voice was sharp, queer. I wondered why it should matter to him about Maxim not loving me. Why did he not want me to know?’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

How soon after her marriage the real-life counterpart of the narrator understood that her marriage had failed and had been a farce is difficult to say. Perhaps after three-four months, which would be February-March 1871. But the fact is that it is, a year after her marriage, in October 1871 that she conceived her child. The exact time when her father-in-law inherited Menabilly. The event that had changed the status of Mary Frances Labouchere from the wife of a queer man to the wife of the queer heir of Menabilly.

Considering this vital turn of events and possible homosexual inclinations of Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., (1845-1872) from whom Daphne du Maurier drew her ‘Maxim de Winter’ and he-Rebecca, it is then no wonder that the obituary of the real-life counterpart made the young man look better than he really was. In the light of the ‘future worldly prospects’ that awaited him should he lived, the obituary portrait created a perfect image that no one could alter.

The obituary was just a continuation of the farce that had started with the marriage of Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., and Mary Frances Labouchere. The matrimony was dully highlighted in the obituary not once but twice to remove any doubts: ‘The hearse containing the body, enclosed in an oak coffin, on which was a plate inscribed – Jonathan Rashleigh, born 26 May 1845, married 8th November 1870, died 8th December 1872.’ […] ‘The deceased gentleman was born at Menabilly May 26, 1845; and married, November 8, 1870, the youngest daughter of Mr. John Labouchere, and niece of Lord Taunton. He leaves issue, an only son, John Cosmo, born 1872.’ (‘Royal Cornwall Gazette’, 21 December 1872)

What the obituary tries to cover was that the marriage of Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., (1845-1872) did not really work out, for it could not really, for Mary Frances Labouchere had married a queer man who did not love her. The fact that Daphne du Maurier expressed through her narrator turned Mary Frances in the below passage:

‘It seemed to me, as I sat there in bed, staring at the wall, at the sunlight coming in at the window, at Maxim’s empty bed, that there was nothing quite so shaming, so degrading as a marriage that had failed. Failed after three months, as mine had done. For I had no illusions left now, I no longer made any effort to pretend. Last night had shown me too well. My marriage was a failure. All the things that people would say about it if they knew, were true. We did not get on. We were not companions. We were not suited to one another. […] He wanted something else that I could not give him, something he had had before. I thought of the youthful almost hysterical excitement and conceit with which I had gone into this marriage, imagining I would bring happiness to Maxim, who had known much greater happiness before. Even Mrs Van Hopper, with her cheap views and common outlook, had known I was making a mistake ' I’m afraid you will regret it,’ she said. I believe you are making a big mistake.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

But it was not just his marriage, the whole short life of Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., had been a farce from his school and university achievements to his service in the militia regiment of Cornwall and Devon Artillery. According to the obituary, he ‘distinguished himself in mathematics throughout his career, generally coming out at the head of his remove in that branch, and obtaining the first prize at his last examination. He gained, whilst in Harrow, about 30 volumes of prizes.’ (‘Royal Cornwall Gazette’, 21 December 1872) In real life, however, there are no records of those achievements in the school’s registry.

Similarly, the statement that ‘at Oxford he commenced his career by gaining the ‘Peel Exhibition’ for classics at Christ Church, and finished his course there by taking honours in the mathematics schools,’ (‘Royal Cornwall Gazette’, 21 December 1872) has no proof for there are no records confirming it. Both mathematics and classics were the two main subjects in the university that every Christ Church student studied.

The link to Christ Church, Oxford and the studying of Jonathan Rashleigh, jun., there is created in the ‘Rebecca’ by mentions of books that Daphne du Maurier placed in certain scenes. The books can be found in the hotel room of Mr de Winter, on the table of the library room which has rows of shelves containing books, and on the bookshelves in the cottage in the woods.

‘No photographs. No snapshots. Nothing like that. Instinctively I had looked for them, thinking there would be one photograph at least beside his bed, or in the middle of the mantelpiece. One large one, in a leather frame. There were only books though, and a box of cigarettes.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

‘The room would bear witness to our presence. The little heap of library books marked ready to return, and the discarded copy of The Times.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

‘So that’s settled, isn’t it?’ he said, going on with his toast and marmalade; ‘instead of being companion to Mrs Van Hopper you become mine, and your duties will be almost exactly the same. I also like new library books, and flowers in the drawing-room, and bezique after dinner.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

‘There was a desk in the corner, a table, and chairs, and a bed-sofa pushed against the wall. There was a dresser too, with cups and plates. Bookshelves, the books inside them, and models of ships standing on the top of the shelves.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier)

The cottage in the woods not only has the books but also a queer musty smell: ‘There was a queer musty smell about the place. Cobwebs spun threads upon the ships' models, making their own ghostly rigging. No one lived here.’ (‘Rebecca’ by Daphne du Maurier) The queer smell and the books are the references to the real-life counterpart of Maxim de Winter - Jonathan Rashleigh, jun.; the place where they are found – the cottage in the wood, – is where two important events had happened: the homosexual romantic relationship and the murder. The presence of ‘the ships' models’ on the shelves of the cottage suggests the way ‘he-Rebecca’ died and as well as provides a clue to some of the background of the queer lover.

About the Creator

Seraphima Bogomolova

Creative entrepreneur/Cinematographic visionary

Screenplays:

‘A Tricky Game', 'Puzzled, and 'Головоломка'

Books:

Головоломка, Puzzled, Задача с неизвестными, Загадка Восточного Экспресса.

Non-fiction books:

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.