The Silver Lining of Surviving

How losing my Mom saved my life.

There is a centuries-old Japanese tradition that involves the art and philosophy of repairing broken pottery. It is called Kintsukuroi, which means “golden repair,” or sometimes Kintsugi, meaning “golden joinery.” When a precious bowl is broken, it is not discarded as something that has lost its beauty or become unworthy. It is carefully, delicately and lovingly pieced back together using a golden lacquer to rejoin the broken pieces. The philosophy behind this practice is based on the belief that the bowl has been transformed into something more beautiful and more resilient than it was before. That its story, told in gold, makes it invaluable in an exquisitely flawed way.

By the time I lost my mom, at 27 years old, I had been 'broken' for almost my entire adult life, and had spent all those years trying to fill those cracks inside me by drinking. My mom's death, however, felt more like a complete shattering of the soul - and yet, because of it, I was given a chance for redemption. The chance to save my own life. To be mended, like Kintsukuroi, into something stronger and better, because my mom was, and always will be, the golden lacquer that holds me together.

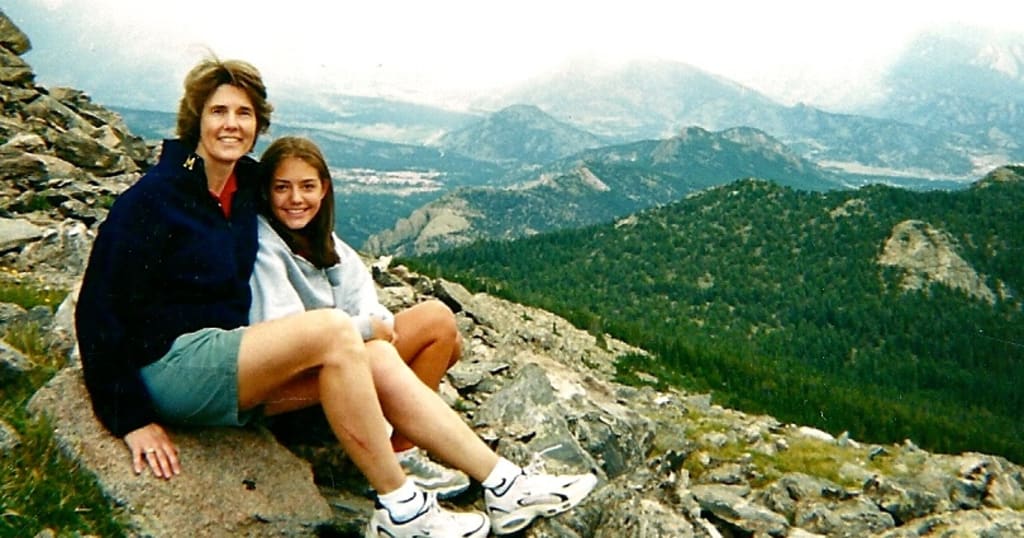

It is maddeningly difficult to find the words that could aptly describe Patricia Hirt Rosenberger; her innate, inherent grace transcended all the boundaries of language. She was one of those people who exuded an aura that made anyone who interacted with her feel as though they were somehow the better for it. She was brilliant at her work as a clinical psychologist at Yale-New Haven Hospital and at the VA Hospital in New Haven. She was incredibly beautiful but carried her beauty without ever acknowledging it - she was in fact oblivious to it, and this just added to her loveliness. She was humble. She was kind to everyone she met. She believed in good manners.

She was my best friend. We shared tastes and experiences in music, literature, and films. I turned to her knowing that when I needed advice, comfort, reassurance, support, or just someone to listen to me, she would make me feel genuinely heard. Her sense of humor ranged from witty to silly, and her laugh was my favorite sound in the world. Perhaps more than anything else, though, she was a woman of faith. She believed in the Christian values of forgiveness, of not judging others, of service to the church, and more than anything, of love. Love that is unconditional: love that never gives up. For my mom, the concept of faith was also grounded in the refusal to give up - on something, on someone, on me. The unshakeable faith she had in me is the reason I am alive today.

One winter afternoon, I was home for Christmas break during my freshman year, reading Proust at the kitchen table, when I heard my father say, “Patty, I’d like to speak with you upstairs.” There was something in his voice that scared me: something that had to do with the strained, tense atmosphere that I had felt as soon as I arrived home. After my parents went upstairs to their room, I crept halfway up the stairs so I could hear what was going on. I listened as my father told my mother that he had filed for divorce. My mom was in such shock at this announcement that she genuinely thought he was playing some kind of horrible joke on her. She only believed it when she saw the letter that my father (who was the senior minister at the Congregational church in our Connecticut town) had sent out to the congregation that day, announcing the divorce. When I saw it, I saw that he had written that the divorce was mutual: a complete lie.

Being a minister's wife (or in my case, a PK - "preacher's kid") meant that our family's social lives revolved mainly around the people who went to my dad's church. So when he made it clear to his parishioners - who were also my parents' friends - that they had to choose between him and my mom (while also making it understood that if they chose my mom, they would need to find another church) they, of course, chose him. My mom lost absolutely every single friend she had, and I was all she had left. I was the one who had to bear witness to her utter and complete heartbreak. I watched as my father continued treat her with contempt and cruelty, and I lost all respect for him. Our relationship was over. My faith in the world as a good or fair place was gone forever, and I felt a continual, lurching panic that would leave me shaking as I tried to find a way to escape from the nightmare my reality had become.

I escaped into alcohol. Midway through my sophomore year, I drank so much that one of my roommates had to call the police, and I was put into an ambulance that took me to the nearest hospital. The doctors decided that based on the amount of alcohol I had consumed, I must have been trying to commit suicide, so I was transferred to the psych ward and put on an involuntary hold for three days. This scenario would be repeated at least half a dozen times within the next two years alone. My mom was summoned to come take me home; the Dean of Students had informed me that I needed to get my life together before I returned. My mom had to pack up my room for me while I sat outside and sobbed. I continued to sob for the entire four hours it took to drive home.

Several weeks later, she was visiting me in a drug and alcohol rehab recovery center; she had insisted it was what I needed to do, and since I wasn’t a student anymore, I honestly did not care where I was and agreed to go. I emphatically changed my mind after I’d been there for two weeks or so, and successfully figured out how best to get myself kicked out. Once again, my mom was summoned to come and get me. This was just the first of three additional aborted rehab stays over the next few years, and about half a dozen outpatient programs. Nothing worked. I could not face the tidal wave of anger and shame and desolation and betrayal. I just kept running from it, and I just kept relapsing.

I was the kind of alcoholic who drank cheap, 100-proof vodka by the liter. It would take me perhaps a single night to polish one off, and then I’d wake up and stagger down to the nearest liquor store and buy more. This continued for several days until I was just too sick to go anywhere. I spent the next several years living at my mom’s, usually relapsing after mere weeks of sobriety. My mom did not know what to do to help me, and I could see how much that scared her. She told me that every single morning when she woke up, her first thought was “I am terrified that my daughter is going to die because of her alcoholism.” Yet throughout all these years of watching me court my own death, she never gave up hope that I would recover someday. She never lost faith.

In 2012, I was 27. I was still drinking. At the beginning of June, my mom started to experience a physical exhaustion that was so debilitating she could just barely manage to push a shopping cart around the grocery store, while I ran around finding the items on her list. She resisted the idea of going to the doctor in hopes that whatever was causing this exhaustion would resolve itself on its own. One night, I came downstairs to where she was half-watching the tv, and when I asked her a question, her response came out slurred and barely intelligible. She never drank because of a propensity to severe migraines, so I knew it was something serious and immediately called an ambulance. She was taken to the Yale-New Haven Hospital, where she worked, and the doctors there started running every test they could think of. None of the results led them to a concrete diagnosis, and she slowly slipped into near-constant unconsciousness. The doctors warned me that there was a strong possibility she would fall into a permanent coma.

I was absolutely terrified, and I did not have the coping skills I needed to deal with this terror because I had spent all of my twenties using alcohol as an escape from the emotions I could not handle on my own. I stayed by her bed 95% of the time, and during the other 5% I ran to the nearest liquor store, bought a flask of the strongest liquor available, and snuck it into the hospital so I would be inebriated enough to stifle the terror that I was about to lose my best friend and the only person who still had faith in me.

After being in the hospital for two weeks - during which time the doctors working on her case continued to fail to come up with a diagnosis for her symptoms - she improved enough that she was allowed to come home. I was supposed to pick her up from the hospital, but I got drunk and forgot, so she had to call each of her friends until she found someone who could take her home. The next night, we were watching a movie together, and she turned to me and asked me why I had gotten drunk at the hospital when I was supposed to pick her up. Every time I drank, she would ask me “Why?” and I could never give her a real answer. But this time, for once, I did. I looked at her and said “Mom, I was terrified that you were going to die, and I cannot survive without you.” She looked at me, gave a small, exasperated sigh and said “Of course you would, Greta. You would be fine.” I was absolutely astonished. I could not begin to conceive of a world without her.

A few nights later, I got drunk again, and I hurled all the anger and fear and depression that was consuming me into words filled with hate and cruelty, then unleashed them on my mother. That was the last time I spoke to her. The next day, her symptoms returned with stunning severity. She returned to the hospital, and expressly forbade me (using my sister to communicate this to me) from visiting her. A few days later, on June 10th, 2012, I drank for the last time. I had tried to make dinner while completely trashed and ended up spilling a huge pot of boiling water on myself; my legs had third-degree burns and the pain was excruciating. Yet the physical pain I was in was acted as somewhat of a distraction from the emotional pain I was in, knowing my mom was dying. Within days, she sank into unconsciousness, and her organs began to fail, one by one. She was put on life support, and after a few days her doctors, who still had no idea what had caused my mother’s body to fail so suddenly, came to the decision that she was not coming back. My sister called and told me to come to the hospital the next day to say goodbye.

On June 20th, I walked into her hospital room feeling as though I was living the nightmare I had envisioned every so often. My mom was being kept alive by machines, and as her oldest child, I was responsible for signing off on the forms that gave the doctors permission to take her off life support. Before they began this process, I spent a few hours by my mom’s hospital bed. Sobbing so hard I could barely choke out the only two words I could manage to say to her: “I’m sorry. I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry.” I knew I was too late: that I had lost this chance forever. When I was ready, my sister joined me, along with my uncle, who was my mom’s older brother, and my aunt. The doctors told us that after taking her off the machines that were performing her vital bodily functions, it might take as long as an hour for her to go. We sat and waited, tears streaming down our faces. I still could not fully believe that this was actually happening. Within fifteen minutes, she gave a long, drawn out breath that made me fully understand the term ‘death rattle.’ In that moment I felt an immense fissure, an enormous rift, a deep abyss spreading through what was left of my humanity. She was giving up, and then she was gone.

Losing the person you love and admire most in the entire world - the person who knows you better than anyone, who knows your entire history as a human being - invokes a kind of emotional pain so acute it is utterly impossible to put what you are feeling into words. The words you come up with just feel hollow and insufficient. Grief, like love, transcends the limitations of language. It is a deep keening moan in the middle of the night, it is the impossibility of being able to control when and where you will start crying, it is the uncontrollable fury at the unfairness of it all, it is knowing that you will never be the same person you were before this happened, that there is no going back.

I recognized that the dividing line between who I was before my mom died, and who I would became afterwards, was about more than just learning how to live without my mom. I understood that I had a life or death decision to make. I could continue to drink in an effort to numb the excruciating pain of living in a world that no longer contained the one person on whom I could depend, the one person who still believed in me. I knew that were I to choose this path, I would die. However, the threat of imminent death wasn’t what really made me decide I would never drink again. The determination and strength I needed to stay sober for the rest of my life came from my mom’s conviction that someday I would be able to do this. She was gone, but I still had the memory of her unshakeable faith in me. I had to cherish that faith and to hold on to it somehow. To keep drinking would have dishonored everything my mom stood for and believed in.

So, for the last nine years, I have been sober, not because I believed in myself, but because of my mom’s undying faith in me. That faith deserves a kind of tribute, and that tribute is my life. The most difficult part of becoming sober, though, was not having to give up the emotional escape route I sought in drinking. It was the cognitive dissonance caused by the knowledge of the cruel paradox I would never be able to make sense of: the fact that if my mom had lived, I would have kept drinking, and I would have died - probably within a year or two. My mom’s death was the most painful experience I’ve ever had to live through, but I know with utter certainty it saved my life. If she had had a choice in the matter - if someone had said to her, “You must choose between your life or your daughter’s life,” she would have chosen my life over hers without a second thought. That is the kind of person she was. That is the kind of mother she was.

This narrative could be read as more my story than my mom’s, but that is because the only way I can attempt to express how much I loved her is by explaining, as best I can, that everything I am today I am because of her. Like the story of the mythical phoenix bird, we evoke, together, both death and rebirth, resilience and renewal.

The silver lining of surviving your worst nightmare is that you gain the knowledge that you can survive anything life throws at you. This knowledge has given me the kind of strength and courage that I always admired in my mom. I try to have faith that she has been with me, somehow, as I have evolved into a person she would finally have been proud of, and I now understand the immense strength it takes to protect the little flame of faith that lives inside you when the howling winds born of anguish and despair are ripping through your soul, threatening to extinguish the source of light you know you must hang on to survive. I have survived. I have kept that flame alive for nine years, and I will continue to protect it for the rest of my life, because it is a remnant of the pure, unadulterated grace that lived in my mom, and that now lives in me.

About the Creator

Greta Rosenberger

I'm currently pursuing my Masters degree in Literature at Northwestern University. Trying to expand my writing into something other than literature analysis!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.