Your Managers Are Suffering a Cranial Rectal Inversion!

The future has been here all the time

Old maps are brilliant because the great mapmakers of the 16th and 17th centuries not only captured the places that were known but gathered as much information from as many sources as possible to try and map uncharted territory. The 1502 Hunt-Lenox Globe is a great example. When they reached a place in unknown maritime waters, they would add “here there be dragons” and illustrate their maps with pictures of monsters warning explorers to beware.

Once again, we are sailing into uncharted territory. It seems as if we all went to bed one night, and when we woke up the next day, everything had changed.

Yet many of us are still operating as if it were yesterday. Most management practices and principles we use today were developed in the 19th and 20th centuries when managers managed hands and workers learned at a different pace.

Digital technology, automation, and globalization have forever changed everything. In the 21st-century knowledge economy, employees produce knowledge and know-how and need to continuously learn in dramatically new ways. Yet managers everywhere are employing management principles and practices as if we’re still in the prior centuries. In response, companies worldwide comprise a movement to change the way they manage people to succeed in today’s knowledge economy.

The greatest mapmakers of old were not the ones who made better maps of places that were known. They gleaned insights about the places yet to be explored and mapped out the uncharted territory.

So that’s what I have attempted to do. My focus is on what happens to all the people—managers and the people they manage—who find themselves in this unknown place where they must learn to manage minds, in a company that tells them they are now responsible for their own learning. It is what I consider the real adventure, which therefore needs to be explored and mapped.

The new world economic order has placed companies at an inflection point in the history of managing people and the way they learn, and managers sit at the exact center of the curve. This curve has been shaped by three major and notable economic paradigm shifts in the past 300 years, each with an attendant management approach and educational system that helped people learn how to do their jobs.

It dismays me that we have this fantastic opportunity now to reimagine work. And that makes most so-called leaders so anxious that they would rather cut, pop, go right past the creative part of that exercise and start thinking about how much square footage do we need? How many desks, how many chairs? But if you do that, and then later you decide I want this kind of future. You may not, you know, you've got the wrong furniture in the wrong offices, you know, you’ve really got to be able to lift your head out from the weeds and think long term about what is going to make our organization meaningful to the world long term. What kind of people are up for that? And how do they want to work? And when you've done that really well, then the desks and chairs will be the easy part. Dr. Margaret Heffernan

The Agricultural Economy: We Managed Backs

The first great economic era was all about land: land for wealth, land for status, land for food. We legally defined private property. Learning was hands-on and on the farm. Education was limited to a few, privately delivered by tutors and small private schools and colleges for the children of wealthy landowners and landed gentry.

We used our bodies and learned to harness the power of oxen and horses. At the most extreme, we enslaved or indentured people to do the backbreaking work. In the early 1800s, picking cotton was one of the most important jobs in the U.S. economy. We managed backs, and almost 90 percent of the population in the Western world worked on farms and in the fields.

The 20th-Century Industrial Economy: We Managed Hands

We harnessed steam power. Electricity became universal. We mass-produced cars, clothing, food, and more on our assembly lines and in sweatshops. The machines took over the farm work and the number of farmers dropped to below 6 percent by the end of the century. Even housework changed when electricity powered washing machines, transformed ice boxes into refrigerators and replaced brooms and dustpans with vacuum cleaners.

Education reforms reflected this change. Public education was meant for everyone, and through a series of legislative decisions, public education reached rich and poor, urban and rural, male and female. Classroom instruction emphasized preparation for careers that were more about hands than backs. Schools emphasized efficiency over individualization in hopes of educating the masses with a curriculum designed centrally by experts that stayed consistent year to year.

Managers and employees learned to do their jobs in an exact copy of the classroom setting in which they learned to learn. The workplace became the school place. Still, change was slow, and the process of learning something often took months and even years. People were in the same place—office or factory—day after day. The predominant method of learning was classroom-based and instructor-led.

It was highly structured training, a model developed during WWI. We developed programs or courses and pushed them out to people we thought needed them. The goal was mass training for mass production, being able to perform the same task or set of tasks the same way for as long as those skills remained useful.

Frederick Winslow Taylor, one of the first management consultants, wrote The Principles of Scientific Management in 1911. He developed what he called the scientific management theory, which used a stopwatch to time the way hands were used at work down to the hundredth of a minute. His time-motion studies tried to emphasize the most efficient way to manage work and optimize work on the assembly line.

Taylor’s research became the standard for managing hands for the remainder of the 20th century. His approach was all about productivity and reducing the time it takes for a worker’s hands to complete a task. Management science was derived from this work and evolved into the MBA degree when companies wanted a scientific approach to management.

The 21st-Century Knowledge Economy: We Manage Minds

In the late 20th century, Peter Drucker was prescient enough to name the people who labored to produce information knowledge workers. What these knowledge workers mass-produced was know-how and ideas.

They spent their days fluidly moving between thinking and talking, meeting, and deciding, researching and writing. Suddenly we depended no longer on backs or hands but brainpower. And yet how we educate, and train adult workers remains the same today.

Here’s a story that illustrates how these three economic paradigms have changed. In 2007, I gave a presentation to the annual gathering of chief information officers (CIOs) at Boeing in Southern California. As the top CIO was leading David into the conference room, she told him that the building they were in had an interesting history. Originally an orange grove, the building was first used as a giant manufacturing facility for producing airplanes. When the demand for planes declined, the huge building was reconfigured into floors, offices, and cubicles. The Boeing employees who worked there sat in front of their computers producing, refining, defining, revising, discussing, and communicating ideas.

Ideas for new planes. Ideas for improving the production of planes. Ideas about related projects that had something to do with planes. In approximately half a century, the same piece of land had been used by workers whose manual agricultural labor produced food; then workers who did highly skilled, industrial-economy manufacturing work that produced planes; and ultimately workers who produced ideas as part of the new knowledge economy.

The Boeing story is an example of evolution through different economies. Now in the knowledge economy, Boeing employees produce ideas, work with ideas, think about ideas, write and talk about ideas. Of course, people then have to turn those ideas into things— planes. But even those people are followed by others who had more ideas about how to market planes, sell them, teach people to fly them, and so on.

Even many of the people we still imagine as being hands-on industrial economy workers are high-tech knowledge, economy employees. Miners have gone high-tech. If you go to the bottom of a coal mine, as former Labor Secretary Robert Reich did more than 20 years ago, you see coal miners using very complicated machines with modern coal-digging equipment, complete with bright LED lights, dials, meters, and finely tuned adjustments that need to be carefully monitored and operated. Even what was once the most manual of jobs has become more highly skilled, requiring people to use their minds and not their hands to produce coal.

This is madness, the way we've been--everything about the way we've been teaching, management does not work. If the first part of forecasts, plan, execute, doesn't work. And we're going around using a 20th century, maybe even 19th-century mindset in the 21st century, and no wonder things are going horribly wrong. Dr. Margaret Heffernan

According to McKinsey, “as many as 45 percent of the activities individuals are paid to perform can be automated by adapting currently demonstrated technologies.” This portends a future where people must take on a different role than they had in the industrial economy. No longer will people be needed to make, operate, fix, or move things. We will have to use our minds to produce work. It may be using technology to augment and increase what we can do, but it is becoming more and more about the production of ideas.

Success in the knowledge economy is about the ability to sift through ideas and identify the ones that can be turned into profitable products and services, and do that in a way that is respectful of the environment and the diverse people who live on this planet.

Taken as a whole, these knowledge workers are the corporate brain. In a flat, digitally interconnected world where 24/7 marketplaces are open, creating a hypercompetitive environment, the corporate brain separates the winners from the losers. It is strategic to make sure that all employees can learn as much as they need of the four types of knowledge—know-what, know-why, know-how, and know-who—anytime and anyplace.

In this knowledge economy, the ability to learn has become the most critical differentiator. Developing that ability is at the center of it all, and managers are the key to making that happen.

Almost All The Managers Are Wrong

When I set out to tackle the role of managers in the 21st-century knowledge economy, we never ventured far from these critical questions: What keeps them up at night? What are their pain points? What’s the biggest problem managers need to solve? We found several ongoing employee issues that are the root of corporate problems and the death of companies that could not evolve fast enough:

- feeling disengaged

- learning on their own; not using company resources

- demanding all things be digital

- needing far more transparency than ever

- wanting collaboration and open communication

- wanting more challenging work that enables them to grow professionally and personally.

Through my research, I found that managers often had a hard time articulating what was keeping them up at night. But they know the current system of management and learning is not helping them compete and succeed in this new marketplace. They are not sure what to call it, but a new model of management and learning, the one we identify as managing minds, seems to be constantly confronting them and is turning out to be far more successful than the old managing hands model.

The companies worldwide that are thriving are adhering to this new model of managing minds. It has proven to be better in many ways; these companies are better able to:

- Increase employee and customer loyalty.

- Create happier workplaces and workers.

- Reduce costly turnover.

- Drive increased profitability.

- Provide measurably improved levels of performance.

- Continuously lead a smarter, more agile workforce.

- Generate more useful ideas.

Successfully managing minds means being able to get the best from people—their talents, thoughts, creativity, willingness to cooperate and collaborate, and feelings of trust, loyalty, and empathy. And that requires winning hearts as well as managing minds. In previous economies, employees might have hated their co-workers, managers, or job, but they were still able to crank out work with their hands. Playing well in the sandbox was not a prerequisite. Try that in a company that needs employees to be continually engaged and learning, working closely with others, and constantly producing with their minds. It doesn’t work.

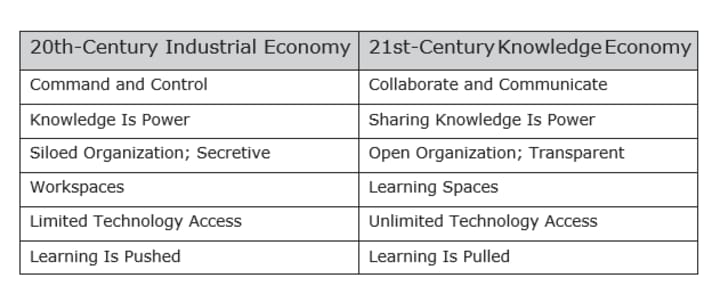

The following table compares attributes of the 20th-century industrial economy model of managing hands with the emerging 21st-century knowledge economy approach of managing minds.

A Tale of 3 Companies

Companies fall into three general groups in relation to managing minds:

- Traditional companies that are still completely managing hands

- Transitional companies that are moving from managing hands to managing minds

- Aspirational companies that are actively managing minds.

Traditional companies are found mainly in developing countries with a strong tradition of using cheap labor to make things. Often this means producing inexpensive items using 19th-century sweat-shop approaches to managing hands. The aspirational companies are experimenting with what works when managing minds. Aspirational companies are most companies trying to change from managing hands to managing minds.

AT&T is a great example of a transitional company that started as a managing hands company (in 1885), evolved structurally, and has more recently realized it had to quickly change—or die a slow death.

In the beginning, there was AT&T and only AT&T. As a government-approved monopoly, the company’s list of firsts in the telecommunications industry is unparalleled. With the first transcontinental line, rotary phone, transatlantic phone service, mobile phone, automated switchboard, and transatlantic phone cable, AT&T was an icon of a company that managed hands and built a telecommunications industry. It all ended in 1982, when the federal government broke giant “Ma Bell” apart, allowing the company to keep only the long-distance and equipment-manufacturing business.

This was the beginning of an intense period of technological change and competition. From that point on, AT&T tried to expand and grow, first into the business of making computers and then, in 1991, buying a cellular company as mobile phones were beginning to take off. Trying to become a one-stop shop for all things communication, AT&T even bought the number two cable television provider. Then in 2002, the big surprise: SBC, the second-largest regional telephone company, bought AT&T. The company, once among the biggest monopolies in the world, the greatest leader in telecommunications technology, had been beaten by a new, disruptive Internet technology that was faster and cheaper. And this is where the transitional part of the story begins.

AT&T’s new competitors included not only Verizon and Sprint but Amazon, Netflix, and Google. Randall Stephenson, chairman, and chief executive knew he had to reinvent the company to compete. When I interviewed him in 2014, he asked 280,000 employees worldwide to start a retraining program. In his mind, it was an easy choice: Take classes and begin to upgrade your skills or limit your opportunities at AT&T to zero. The company knew that a large portion of the workforce needed to learn the new digital technology, and fast. In response, Stephenson rolled out a program called Vision 2020 that combined online programs and classroom-based courses to prepare employees to work with AT&T’s cloud-based system, scheduled for implementation in 2020.

The change in technology is profound. It will make copper wires, phone lines, switching equipment—and much more—obsolete, along with the related work skills. AT&T employees must learn a full range of new skills relating to everything from digital networking and cloud technology to virtualization and data science. New products need to be developed, marketed, and successfully implemented.

The 2020 date is only the beginning. According to Randall Stephenson, “There is a need to retool yourself, and you should not expect to stop.” Employees are expected to take as much as 10 hours per week of online learning or find themselves “obsolete” with regard to ever-changing technology. In other words, they need to become continuous learners. They need to take responsibility for learning what they need to remain valued in the company.

Vision 2020 is a bold idea for a giant corporation that needs to change or, in Stephenson’s words, “If we can’t do it, mark my words, [by 2022] we’ll be managing our decline.”

Some AT&T employees are fully committed, like one product manager responsible for smartphone software. With company assistance for tuition, she leaves work at 7 p.m., studies at home until midnight, and spends Saturdays and Sundays getting her master’s degree in computer science. Soon after the start of the program, almost half the workforce, mostly managers, signed up, most taking online courses in web design and development, programming, app development, and data analysis.

Not everyone is looking forward to a new high-tech career at AT&T. Many employees who have been with the company for years are looking forward to getting a “golden handshake” and retiring early. The company estimates that the number of retirees and people who leave because they don’t want to go through the coming changes will make AT&T a leaner operation, with one-third fewer workers. And, because changing from a company that needs wires fixed and ditches dug to one specializing in cloud-based software cannot happen overnight, many employees will reach retirement age while the changes are occurring and will never experience the “new AT&T.”

For the employees who are looking forward to working with the new organization, the Vision 2020 program is constantly at the forefront of their work. Weekly emails are accompanied by video programs about online learning courses. There is a company website where employees transitioning from an analog company to a software-based one can find new careers and check to make sure they have the required courses, certificates, or credentials.

Coursework and grades are tracked, and new, related courses are recommended. Performance reviews will contain the information on these courses and note whether the employee is willing to help the company succeed by continuously learning. Promotions will be influenced, in part, by whether the employee keeps learning.

Not many companies can make the transition from managing hands to managing minds without some pain. AT&T is an example of how technology, automation, and globalization can force even the oldest and largest of companies to pivot and try and become a company that can compete and succeeds in the 21st-century knowledge economy.

AT&T’s transition will require the total commitment of the company—every aspect of organizational life must support and encourage learning. Everyone must begin to actively manage minds.

The key to AT&T’s success, as with all knowledge economy companies, will be whether managers can make the shift from managing hands to managing minds.

Mitsukoshi, Inc. is a Japanese retailer that has been around since the 1600s. The company is constantly changing and innovating, which is likely why it has been able to survive this long. Mitsukoshi’s approach to changing rooms is another aspect of that, as it invented the “intelligent fitting room.”

The retailer noticed that its staff was constantly running back and forth to help people in its changing rooms, creating chaos and reducing productivity. So, the retailer, which is similar in popularity to Target, invented a changing room that let customers check out sizes and clothing by themselves, without disturbing the staff.

Once we recognize that the problem is using an outmoded way of managing people, we must ask, “How do I evolve from the old style of management—managing hands—that no longer seems to produce the results I need, to this new approach called managing minds?”

About the Creator

David Grebow

My words move at lightspeed through your eyes, find a synaptic home in your mind, and hopefully touch your heart! Thanks for taking the time to let me in.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.