Demonetising Russell Brand Doesn’t Make YouTube the Good Guys

For all its PR spin, YouTube’s stance on the controversial comedian is hypocritical at best.

The moment comedian-cum-wellness guru Russell Brand was outed as an alleged sexual predator, the media world rushed into spin control.

A regular fixture on television, in film, and on the front pages of tabloids for decades, Brand is now accused of sexually assaulting, emotionally abusing, and even raping multiple women– including a teenager — in a years-long pattern of abuse, according to a meticulous investigation by Britain’s venerated daily broadsheet, The Times of London, and Channel 4’s long-running current affairs television program, Dispatches.

The allegations were as damning as they were deeply researched, the result of a four-year investigation into incidents that were commonly discussed among industry insiders but never, until now, aired publicly.

Britain’s television networks, which Brand has appeared prolifically on over the years, quickly moved to review Brand-related materials in their online and catch-up archives. The BBC removed some material from their iPlayer and BBC Sounds platforms. Channel 4 sent a stronger message by removing all content featuring the comedian in their entirety. Both networks pledged an immediate review of Brand’s conduct while employed by them.

YouTube took a different tack.

The video platform left his content — including bizarre conspiracy-laden protestations of innocence in which he blamed an unholy cabal of mainstream media outlets, the British Government and ‘big tech’ for his woes — intact.

A YouTube spokesperson addressed the controversy by announcing that Brand’s video channels would be demonetised, referring to the much-maligned technique for punishing content creators for publishing unacceptable content.

The practice is loathed by content creators for its heavy-handed application when it comes to including short, copyrighted video or audio clips to accompany a news story. In any other medium, this would constitute fair use. Other times, the infringement could simply be a grown adult sing the word ‘fuck’ when speaking to other grown adults. Or, in nonbinary YouTuber Caelan Conrad’s case, for saying the word ‘queer’.

In simple terms, the policy prevents a video from being eligible to earn advertiser revenue, should YouTube decide, sometimes clearly, sometimes arbitrarily, it is inappropriate.

Less frequently, the platform applies demonetisation to videos that spark a public backlash. Such is the case for the men’s rights channel Fresh ’n’ Fit. Within three years, hosts Myron Gaines and Walter Weekes garnered 1.5 million YouTube subscribers who regularly tune in for defences of their bro, Andrew Tate, promotion of hustler culture, interviews with far-right figures, and generalized misogyny.

(Unsurprisingly, the Fresh ’n’ Fit boys think Brand has been badly done by, questioning whether the alleged victims are real and mocking their agency by joking that “We should start a movement where men take back consent after we fuck a bitch.”)

Daily Wire host Candace Owens also earned demonetisation for persistently attacking and misgendering trans people.

In both cases, as with Russell Brand, YouTube claimed the high moral ground, patting itself heartily on the back, saying that “if a creator’s off-platform behaviour harms users, employees, or ecosystem, the platform may take action to protect its community, including by suspending monetisation.”

This protective action notably does not include removing the harmful content. Despite protestations of being ‘canceled’, both channels remain available and intact on YouTube.

The policy YouTube’s PR team relies on in these cases is its Community Guidelines, which guard against a range of practices deemed harmful and deceptive including nudity, spam, violent content, bullying, and hate speech.

To read YouTube’s media statements, protecting the community is the company’s primary concern when deciding whether to demonetise. Any closer inspection tells a different story.

Demonetisation comes at literally no cost to YouTube, even marginally boosting profit margins by providing content for free that would otherwise have seen them pay out small percentage of advertiser revenue.

But still they provide it.

Russell Brand’s entire unhinged catalog is still available on YouTube and continuing to grow. Even after demonetisation, Brand still publishes new content on the site, with a predictable and growing emphasis on his own persecution and the straw man argument about a vague “media war against free speech” that he used to sidestep the credibility of the allegations against him.

YouTube is straddling the line, seeking to distance itself from the controversy but not its controversial subject.

The simple view is that the company doesn’t want to lose eyeballs on Brand’s content, which is only gaining more attention in the wake of the scandal. Brand’s conspiracy-laden self-defense video protesting his innocence has garnered more than 180,000 views, eclipsing even his heavily promoted interviews with Ben Shapiro and Tucker Carlson. YouTube’s algorithm then suggests further viewing options for Brand’s followers which link to other, monetised (hence, profitable) videos from Brand’s ideological fellow travellers.

But there is more at play for YouTube than simply keeping audiences coming back for more conspiracy theories and dodgy wellness advice.

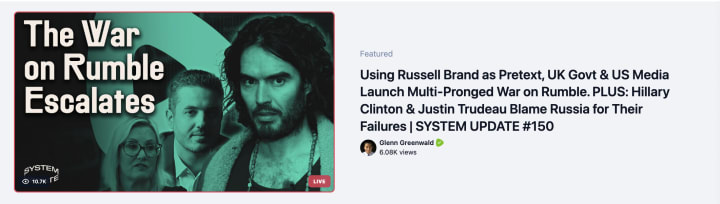

In the contest for attention from the alt-right, the world’s most dominant video-hosting platform faces insurgent competition from Rumble. Established in 2013, Rumble provided a more deliberately conservative leaning than its larger competitor, as evidenced by its refusal to take any action against punitive action against Brand. So far, it has stuck by the decision, despite some major sponsors — including Burger King, Asos, and HelloFresh — removing ads from the platform in response.

The protest seems unlikely to faze Rumble’s owners who see the scandal as a longer game, an opportunity to peel even more far right viewers away from YouTube. As of this writing, the featured story on Rumble’s home page is a piece by journalist Glenn Greenwald decrying the British and American governments’ “Multi-Pronged War on Rumble”.

If, as YouTube’s media releases imply, the content is harmful and problematic, then why are they still available on the platform where they can presumably cause further harm?

If the argument for leaving them untouched is because Brand is innocent until proven guilty, then why punish him financially in the first place?

Whether YouTube’s demonetisation of Brand is right or wrong is a complicated matter of perspective. His commentary on Covid-19 and other vaccines is, at best, denial-adjacent. His fawning platforming of far-right figures such as Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro, and Tucker Carlson is, at least from my progressive perspective, egregious.

But they have nothing to do with the current allegations he is facing.

Even as the intensity of the controversy grows — police in London have now launched a formal investigation — and as Brand’s accusers and the original reporting seems increasingly credible, none of this absolves YouTube for profiting from a scandal while trying to stand on a higher moral ground above it.

No matter how they try to spin it, YouTube is not the hero of this story.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.