The UK's Worst Female Serial Killer: The Chilling Case of Mary Ann Cotton

The 'Dark Angel' of Death was a 'monster in human shape'.

Mary Ann Cotton, she's dead and she's rotten,

Lying in bed with her eyes wide open.

Sing, sing, oh what should I sing?

Mary Ann Cotton, she's tied up with string.

Where, where? Up in the air.

Selling black puddings, a penny a pair.

Mary Ann Cotton, she's dead and forgotten,

Lying in bed with her bones all rotten.

Sing, sing, what can I sing?

Mary Ann Cotton, tied up with a string.

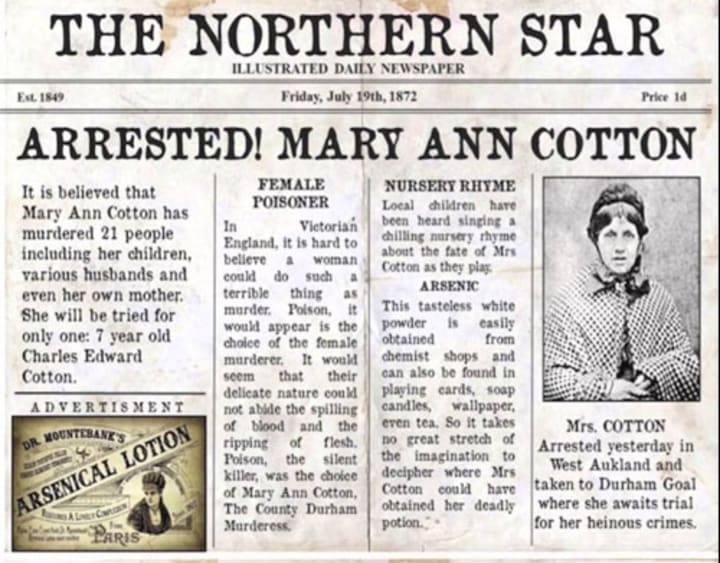

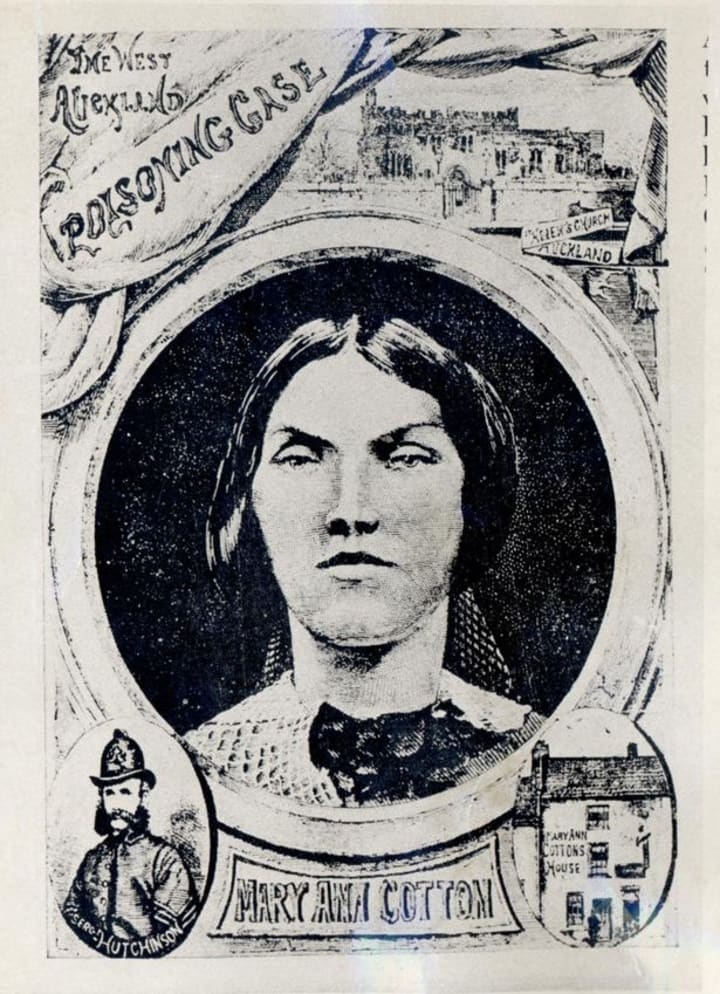

Born on the 31st of October 1832 in County Durham, Mary Ann Cotton was a notorious British serial killer. She was convicted of murder after poisoning her stepson, although it's widely believed that she was responsible for the deaths of around 21 other victims.

There isn't much information regarding Cotton's early childhood. However, in 1842, when Cotton was only 10 years old, her father, Michael Robson, fell 150 feet down a mine shaft. He subsequently died. His body was returned to the family - his wife, Margaret, his daughter, Mary, and his son, Robert - in a burlap sack. This event was undoubtedly traumatising for the family, but it also may have triggered a realisation in Mary that life was disposable, and death was meaningless. Instead of being shown compassion after the tragic death of Michael, the family was evicted from their home as it was connected to Michael's job as a miner. Her mother remarried a year later, and at the age of 16, Cotton left home to train as a nurse in a nearby village. She pursued an occupation that requires compassion, understanding, and empathy. She accepted a role that gave her access to vulnerable patients, and also allowed her some understanding of the medical field.

Cotton married her first husband, William Mowbray, in 1852 at the age of 20. The couple had five children, yet none of the births or the deaths were registered; it wasn't a legal requirement until 1874. All of those nameless and forgotten children succumbed to alleged stomach fevers. Margaret Jane, their first registered child, was born in 1856, but she died four years later in 1860. Isabella was born in 1858, and a second daughter named Margaret Jane was born in 1861. A son, named John Robert William, was born in 1863, and he died in 1864 of gastric fever. Mowbray himself died in 1865 of an intestinal disorder. After his death, Cotton collected the money from her husband's life insurance, as well as that of her son's.

Cotton moved to Seaham Harbour with her daughters, Isabella and Margaret. She quickly began a relationship with Joseph Nattrass. Despite surviving longer than most of her siblings, Margaret died after contracting typhus fever, leaving Isabella the sole survivor of her mother's murderous nature. Cotton began working at Sunderland Infirmary, and sent Isabella to live with her mother.

While working at the infirmary, Cotton met George Ward. He was one of the patients under her care. They married in 1865, but he died the following year after suffering paralysis and intestinal problems. The attending doctor who was treating Ward stated that he had been very ill leading up to his death. However, his passing was surprisingly sudden. Cotton collected the money from his life insurance.

Cotton was then hired by James Robinson as a housekeeper in 1866. His wife had recently passed away, and a month after Cotton began working for him, his infant son, John, died of gastric fever. Robinson, grieving after the loss of his beloved wife and child, turned to Cotton for comfort. She subsequently fell pregnant again. At the same time, Cotton's mother, Margaret, became ill with hepatitis. Cotton, who had a history of nursing, went to care for her. Margaret started to recover from her illness, yet she began complaining of a new ailment: stomach pains. Margaret died nine days after Cotton's arrival.

Isabella, who had been living with her grandmother, returned to the care of Cotton, and went with her mother to Robinson's home. She also developed stomach pains, and died soon after. Cotton made a claim on her life insurance policy. Two of James's children, named Elizabeth and James, died under similar circumstances. The three children passed away in 1867, yet it wasn't a year of sadness for Cotton and Robinson; the two married later that year. The couple's first child together, Margaret Isabella, died in 1868, and their second child, George, was born in 1869.

Robinson grew suspicious of Cotton's insistence that he took out a life insurance policy, and he later discovered that Cotton had amassed debts of £60 without informing him, as well as stealing £50. In addition to this, Cotton had forced Robinson's older children to pawn the family's valuables. She was forced from the property, and he retained custody of their son, George.

Now homeless, a friend of Cotton's introduced her to her brother, Frederick Cotton, who had lost two of his four children. The pair bigamously married in 1870, and their son, Robert, was born in 1871. While married to Frederick, Cotton learned that her former lover, Joseph Nattrass, was living nearby. His marriage had failed. Cotton and Nattrass rekindled their relationship. Frederick died of gastric fever in December 1871, and Cotton promptly claimed the life insurance payout.

After Frederick's death, Nattrass moved in and became Cotton's lodger. Cotton accepted work as a nurse to an excise officer recovering from smallpox, and Cotton fell pregnant with John Quick-Manning's child. Two more of her children died of gastric fever in 1872, as did Nattrass. His death occurred after he revised his will and left all of his belongings to Cotton.

A parish official, Thomas Riley, asked Cotton to help nurse a woman with smallpox. Cotton informed him that her son, Charles Edward Cotton, was causing her issues in accepting the role, and chillingly told him that 'I won't be troubled long'. Five days later, she informed Riley that Charles had died. Riley convinced the doctor to delay writing the death certificate, and approached the police with his concerns. Cotton attempted to claim the life insurance payout, but she was informed that no money would be handed over until a death certificate had been officiated. An inquest into Charles's death determined that he had died of natural causes.

The doctor who attended Charles, named William Byers Kilburn, became suspicious of Cotton's involvement in the deaths of those closest to her. He had kept samples from Charles, and tests revealed that those samples contained traces of arsenic. Arsenic was tasteless, meaning that Cotton's victims would have been unaware of the fact that she was poisoning them. Furthermore, the effects of arsenic poisoning, such as vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain, were similar to common medical conditions at the time, including gastroenteritis. The police were informed, and Charles's body was exhumed. Cotton was arrested and charged with murder, but the trial was delayed until her final child, Margaret Edith Quick-Manning Cotton, was born in 1873.

Cotton's trial began on the 5th of March 1873. She was found guilty of murder, and was sentenced to death. She was hanged at Durham County Gaol on the 24th of March 1873. Her execution wasn't quick or painless. The rope wasn't rigged correctly, so her neck didn't break. Instead, Cotton slowly strangled to death, with the executioner being forced to push down on her shoulders to increase the pressure around her neck. It took over three minutes for Cotton to die.

Mary Ann Cotton never confessed to any of the murders, so the true number of her victims is unknown, but it's assumed that around 21 people lost their lives because of Cotton. She was considered to be Britain's deadliest killer until Harold Shipman committed his crimes. Cotton betrayed the trust of her children, who were vulnerable, defenseless, and innocent, as well as her husbands, her other family members, and her friends. Their lives were disposable and meaningless, and their deaths allowed her to gain financially, and move on to new victims.

Over 100 years after the killings, in the early 1990s, Durham Jail was modernised, and the graves of some of those who had been executed there were disturbed. This included the grave of Mary Ann Cotton. A pair of her shoes were found along with her remains. Her body was taken, along with the others removed from the site, and they were all cremated.

About the Creator

Charlotte Williams

Instagram: @charmwillwrites

Creative Writing Grad from the UK.

Interested in myths, and true crime.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.